The Seasons is the sort of thing that can happen when talented and creative people get together and have a shared interest. The group will expand as a vision and its needs materialize and come into focus, in this case, the production of a new baroque opera focused on the weather. The assembled team is extraordinary. Let’s take a look at the opening credits in the program book for The Seasons (my comments in parentheses):

Music by Antonio Vivaldi (a draftee by the creative group, remember the 1700s, though Vivaldi came to praise the seasons, not to bury them)

Based on “The Four Seasons” with additional arias and ensembles by Vivaldi (the opera runs an hour longer than Vivaldi’s famous four violin concertos that include Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter)

Libretto by Sarah Ruhl (also a poet, playwright, and essayist)

Co-conceived by Anthony Roth Costanzo (performer for the first time while also general director/president of Opera Philadelphia) and Sarah Ruhl in collaboration with Pam Tanowitz (choreographer) and Zack Winokur (director)

Developed by SCENE and AMOK

The Cosmic Weatherman (John Mburu) warns of seasons out of order. Photo by Steve Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Then, the contributor list goes on (before I get to the singer-actors in the opera):

Conductor – Corrado Rovaris

Music Director: Stephen Stub

Musical advisor: Grant Herreid

Dance Rehearsal Director – Mark Crousillat

Costume Designer – Carlos Soto

Co-costume Designer – Victoria Bek

Co-set Designer – Jack Forman

Co-set Designer – Mimi Lien

Lighting Designer – John Torres

The Poet (Anthony Roth Costanzo) sings in light snow and a backdrop of mountains made of soap. Photo by Steve Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Well, what has this team wrought, and does it work in performance? First, let’s set the stage, there are five characters gathered at a farm to let the weather and nature spark their creativity, and an additional five dancers, plus an orchestra and children’s chorus – it is an opera constructed of existing Vivaldi music and arias with a modern story and new words (and includes some clever, environmentally friendly special effects). The plan is disrupted as the seasons appear out of order and are marked with weather extremes, as The Cosmic Weatherman foretells in the prologue. The vision is grand and timely, the relationship between people and the weather.

The Poet – Anthony Roth Costanzo

The Farmer – Abigail Raiford

The Cosmic Weatherman – John Mburu

The Performing Artist – Whitney Morrison

Painter - Kangmin Justin Kim

The Choreographer – Megan Moore

Dancers: Maggie Cloud, Mark Crousillat, Taylor Labruzzo, Brian Lawson, Stephanie Terasaki, Anson Zwingelberg

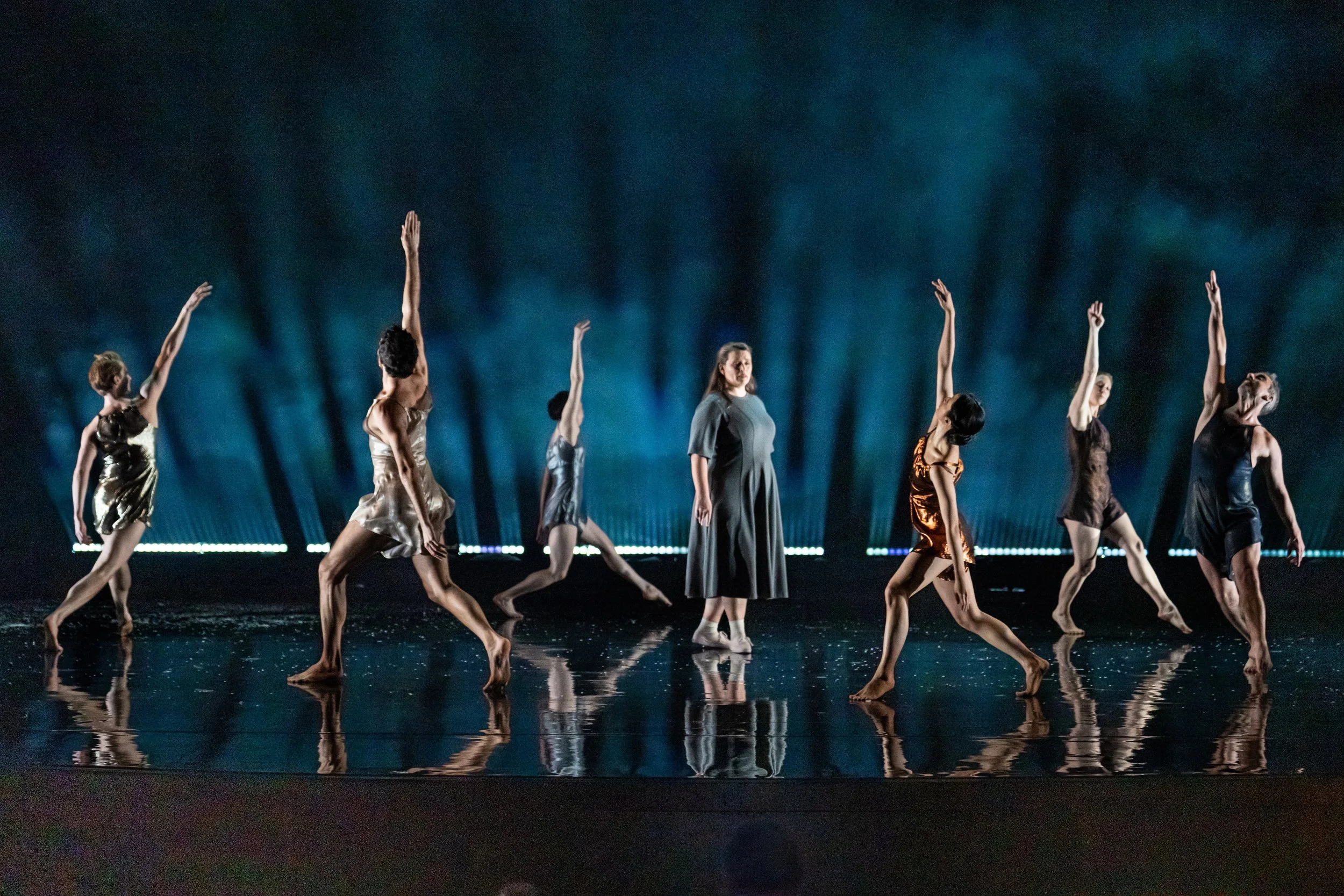

(l to r) Dancers Taylor LaBruzzo, Maggie Cloud, Brian Lawson, Anson Zwingleberg, Stephanie Terasaki, and Marc Crousillat. Photo by Steve Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

While both the words and music are critical to an opera’s success, my personal favorite is the music. If the music is great, I can forgive a lot. Vivaldi’s music is great. Though best known for his musical compositions, he also wrote what is estimated to be over 40 operas, not often performed today and many lost to history. I have enjoyed “The Four Seasons” for most of my life, simply as a good listen with lively and beautiful music. In preparing for this opera, I discovered that the music was composed to reflect sonnets written for each season, perhaps by Vivaldi himself. Vivaldi was trying something relatively new, attaching human sensorial impact to orchestral music, to hear his music and feel a connection to the weather. As OP’s The Seasons is chamber-sized, the Perelman Theater was selected as the venue, whose pit was filled with twenty members of the Opera Philadelphia Orchestra, led by Maestro Corrado Rovaris. The music seemed played to perfection, fully displaying the beauty of Vivaldi’s music and arias while adding emotion to scenes on stage without distracting from the action on stage or competing with the singing. Kudos to solo violinist Max Tan for excellent playing, and librettist Ruhl is to be cheered for making her story and words fit so well with Vivaldi’s music.

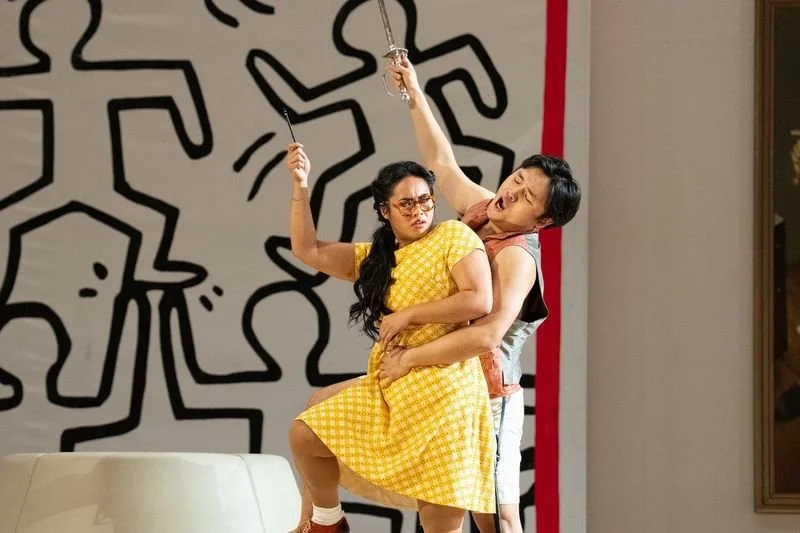

Flutist/dancer Emi Ferguson and The Painter (Kangmin Justin Kim) above a fallen Poet (Anthony Roth Costanzo). Photo by Steve Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

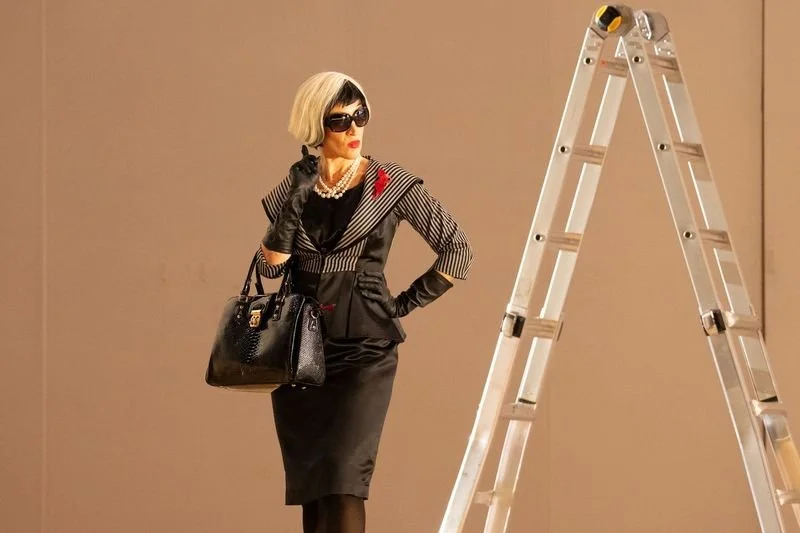

If you like baroque music and melisma in your arias, this opera is for you. OP assembled an outstanding group of singers for this production, led by world superstar countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo. Several of his arias were breathtakingly beautiful as Vivaldi’s vocal works provide a perfect showcase for the arresting emotional presence that is conveyed by his extraordinary voice. He is also an accomplished actor and stage presence who gave a convincing portrait of a troubled poet who falls for The Painter, played by talented countertenor Kangmin Justin Kim, who sang well as he yields to his feelings and a hot relationship with the poet. There were many comic touches in the opera, with soprano Abigail Raiford’s farmer making a salad while recording a video for Instagram being a hilarious highlight; her voice and singing were also highlights. While these characters in Ruhl’s words were more attentive to the weather inside them than outside them, The Performer, played by soprano Whitney Morrison, had a clear-eyed view of the changing seasons (“What the hell is it doing snowing in summer!”). She sang beautifully, expressing anger and fear, imploring the others to join her on the watercraft she had put together from garbage. Perhaps the most sympathetic character was The Choreographer, played by mezzo-soprano Megan Moore, who was not yet ready to commit to a relationship with the Farmer because of a recent breakup. She sang well with affecting emotion and became a special point of sadness.

left - The Performance Artist (Whitney Morrison). right - The Farmer (Abigail Raiford). Photo by Steve Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

The Cosmic Weatherman, sung by bass-baritone John Mburu, appeared at the beginning, several times during the opera, and at the end to proclaim the dangerous period that climate change had brought upon the world and exhorting his listeners to fight, leaving no doubt about the message this opera wished to convey. A ray of hope among losses was offered at the end when the Commonwealth Youth Choir sang an ensemble piece by Vivaldi beautifully under Program Director/Conductor Dominique DeSilva.

The dance element, enriching the opera with its portrayal of the weather events, was one of its most enjoyable aspects. The synchronized ballet and individual performances were in the right mood, flowed smoothly with grace and pinpoint execution, and were visually beautiful. The opera featured an outstanding flute solo by Emi Ferguson while dancing on stage with the dancers. It took me awhile to believe that a dancer was the flutist playing the piece with such beautiful execution. Her performance was mesmerizing and joyous.

The Choreographer (Megan Moore) surrounded by dancers. Photo by Steve Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

The staging of the opera used simple sets, with a screen in the rear, and dropdowns overhead, illuminating place and mood by use of special effects of lighting, projections, and snowflakes and bubbles, used effectively for the most part, slightly distracting at times - large soap bubbles. Co-creator Costanzo worked with Jack Forman, an MIT doctoral student in materials science, to have special effects that were environmentally friendly and safe for the players on stage, such as making snow showers from soap. The lighting and projections were used effectively to portray the seasons gone wrong. My favorite was the icicles that hung from strings about the stage in different moving patterns, particularly as an adornment for Costanzo’s soulful singing. When the opera premiered at Boston Lyric Opera in March, technical issues prevented many of the planned special effects from being employed.

l to r: The Farmer (Abigail Raiford) and The Choreographer (Megan Moore) during a fire. Photo by Steve Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

The Seasons’ artistic entertainment was outstanding in most regards, and the opera can easily be recommended for those high points alone. How well it delivered its message of preoccupation while outside disaster looms is open to question, and frankly, I struggled with this issue. Director Winokur did a good job of structuring the opera’s flow and employing the special effects. Seasons and their weather patterns are a challenge to portray on stage, even with the help of Vivaldi’s music and the dancing. The director and libretto did an excellent job describing the weather inside and outside the characters, but for me, less well in portraying the emotional connection between the two. The weather was already disjointed as the characters appeared, not something new; we didn’t get a chance to feel their connection to nature and its healing effects. If one reads the synopsis, the weather events were there that should have emphasized the threat that was building, a weather change evoking a lover’s quarrel and a winter storm raising survival as an issue. There were a lot of weather events, perhaps too many, packed into the last third of the opera that perhaps needed more dramatic development. Also, in the libretto much more was explained than I could take in watching and listening with so much going on, music, singing, acting, and special effects as multiple weather events exerted themselves. Viewing this, for whatever reasons, I was more concerned with what was happening to the characters in the moment than experiencing a sense of loss and impending doom; the emotional center of the opera was the weather inside, for me.

The Seasons was a pleasure to attend, and I definitely would not want to have missed this extraordinary assembly of talent. I’m not sure that viewing the opera will awaken many from what librettist Ruhl describes as their helpless numbness when confronting climate change. My wife disagrees, and the Cosmic Weatherman did his best to raise consciousness – and I hope I’m wrong. Personally, I went home feeling highly entertained by the great music, singing, dancing, and compelling individual stories as well as the atmospheric snowflakes and bubbles. But perhaps, my sense of doom over the future arising from global warming was already substantial, and my sense of helplessness too strong for the Cosmic Weatherman alone to penetrate.

The Fan Experience: Performances of The Seasons were scheduled for December 19, 20, and 21 in the Perelman Theater and were sold out. The opera was sung in English, Italian, and Latin with supertitles in English. The opera lasted a little over two hours, including a 20-minute intermission. A pre-opera discussion was held one hour prior to performance with Lily Kass and guest Jack Forman.

Next up for Opera Philadelphia is the world premiere of Complications in Sue on February 4, 5, 6, and 8. Pick your price ticketing as low as $11 for any seat remains in effect this season.