Before Opera Philadelphia’s Festival O22, there was O19, O18, and O17; sadly, O20 and O21 were precluded by the COVID-pandemic. Festival O17 that began the 2017-2018 season was inspired by an OP analysis that suggested today’s audiences favored binge watching. In moving to a Fall festival format to open their new seasons, OP not only wanted to provide an opera-binge opportunity, but a variety of options strategically selected to push the boundaries that would help define the coordinates for modern opera. In this year’s program book, Opera Philadelphia’s Board Chair Stephen Klasko says that O22 is the company’s “fourth exploration of the future of opera”. The Opera on Film addition to the festival was an example of OP pushing the boundaries; its inclusion in the future will depend on OP’s analysis of fan response to O22. This blog post covers two productions in O22, The Raven and Black Lodge, where opera boundaries are pushed even further, maybe beyond the limits?

Let’s start with The Raven (2012), “a staged, 40-minute chamber opera with 12 players”, by renown Japanese composer, Toshio Hosokawa; Edgar Allen Poe’s eponymous poem constitutes the entire libretto. Both the audience and performers were on the stage of the Miller Theatre during the performance. Not enough pushing? Entering the theater each attendee was given the choice to participate in a greater or lesser degree in a 30-minute pre-performance exercise, and we were assigned to a small group, each led by a different Lenore, six in all. My Lenore was a healing Lenore who questioned us about daemons in our lives that led us astray (including Matt Damon), and ways to seek forgiveness and healing. I suspect pushing the boundary into an interactive area is likely on target as a direction of the future. Audiences now have seen so many stories on television and the movies, there seems to be an undercurrent emerging of people wanting to be involved with their entertainment.

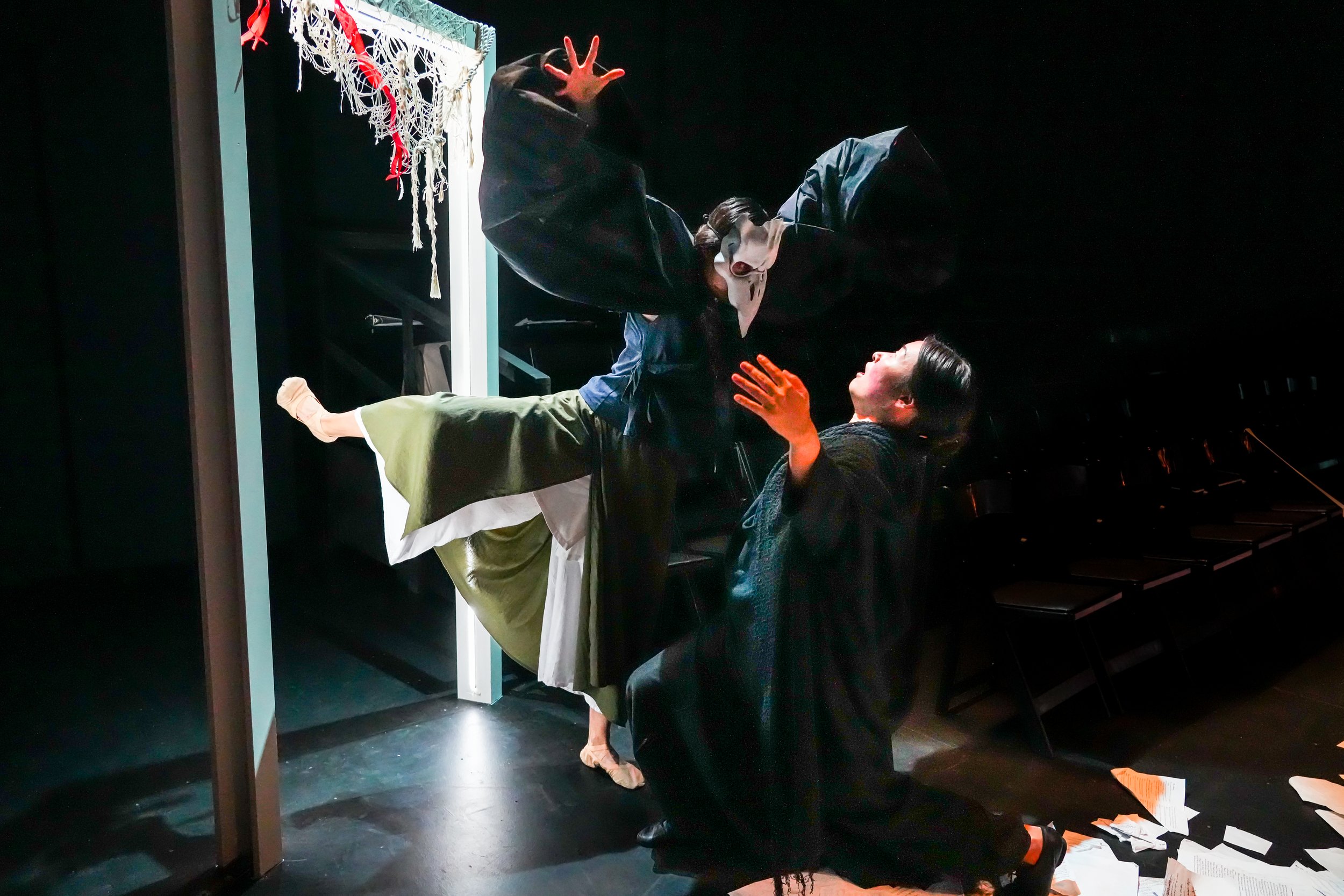

Kristen Choi as the narrator/singer in Toshio Hosokawa’s The Raven. Photo by Steven Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

The nature of the other Lenores was not revealed to us except for a daemonic one who led another audience group momentarily crashing through our space. Given the real/otherworld tension in the poem, having spirits guide us seemed natural. This lead-in was amusing and fun and did give cause to consider more deeply who Poe’s Lenore was; the poem only tells us she was a maiden who has died. Director Aria Umezawa worked with a local company, Obvious Agency, to help conceive and staff the piece, demonstrating Opera Philadelphia’s emphasis on community connection. They came to realize that we know little of Lenore, only that she was a rare and radiant maiden who the narrator of the poem had lost. The creative team started to think of Lenore as everyone and each person as consisting of many Lenores. The composer considered his work Noh-like (Noh is a classical Japanese theater style). The creative team selected Noh-like elements to work with the music and vocal lines projecting the fear, suffering, and anguish of the poem narrator’s dream-state ruminations, having lost Lenore.

Photo 1: Dancer Muyu Ruba in Raven’s mask displaying in front of the narrator/singer Kristen Choi. Photo 2: Dancer Muyu Ruba (sans mask) as spirit Lenore attempting to console narrator/singer Kristen Choi. Photos by Steven Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

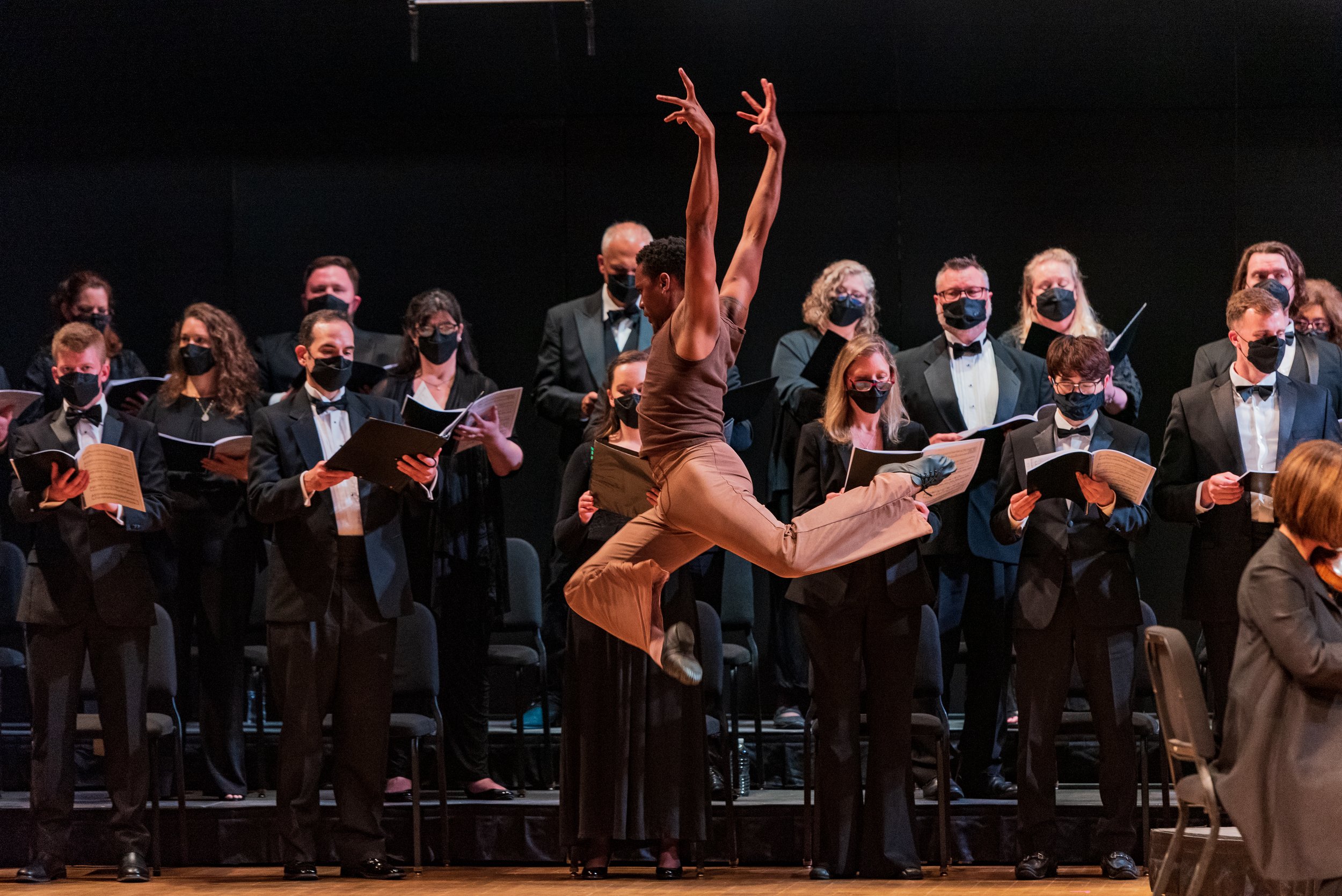

The pre-performance was closed by the Lenores leading us from our curtained areas in the bowels of the Miller to the stage of the Miller where bleacher seating was arranged in a U-shape with the orchestra at the open end; the floor was swamped with sheets of paper covered with writing or typing and old photos, with some items torn, and had door frames at the corners where Lenores entered and exited. The central characters on stage were the narrator played impressively by mezzo-soprano Kristen Choi and the Raven played by dancer Muyu Ruba. By her movements on stage and her great vocal dexterity Ms. Choi sang the libretto, intermittently reciting the poem’s lines, varying pace and volume of each to display anguish over the loss of Lenore and the inability to move beyond it; doing this for about 40 minutes non-stop must present quite a challenge for an opera singer. Despite the seriousness of the opera, it was quite a pleasure to see and hear Ms. Choi up close. I had the pleasure recently of seeing her perform in OP’s Rigoletto and in OP’s film feature, “TakTakShoo”. Ms. Muyu was convincing as she constantly displayed bird-like movements around the stage and in her confrontations with the narrator/singer. She removed her mask for a brief period near the end, reverting to a Lenore, to confront the narrator, a move open to interpretation and maintaining the ambiguity of the poem. The group of eight Lenores (Joseph Ahmed, Ang(ela) Bey, Vitche Boule-Ra, Makoto Hirano, Daniel Park, Minou Pourshariati, Pax Ressler, and Muyu Ruba) largely moved in the periphery to provide anchoring and framing for the two central characters.

Photo 1: A healing Lenore (Pax Ressler) interacting with an audience group. Photo 2: Spirit Lenores sorting through papers and photos at the beginning of The Raven. Photos by Steven Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Composer Hosokawa’s music with built in silences tended to feature solo instruments or sections of the 12-piece ensemble to strike notes to color the modulating action on stage. His music to me paints a series of threatening, rapidly changing murals colored with suffering and anguish. There is a sense of emotional purity in the notes played by the featured instruments and orchestral sections. Kudos to the ensemble and Conductor Eiki Isomura. I thought that much of the natural musicality of Poe’s language seemed lost with this treatment. On the other hand, whenever I read “The Raven” I am so impressed with the perfection of its rhyme and rhythm that I don’t connect completely with feelings evoked. Hosokawa’s composition gives full vent to the emotional content of the poem. If you have read the poem (who hasn’t?), experience the opera to complete your experience of the poem. If you are lucky, there might even be an interactive pre-performance event.

Usually, I do some preparation for an opera performance before attending, at least reading the summary of the first act to make sure I have all the players straight. I went into Opera Philadelphia’s premiere of Black Lodge only knowing that it was a rock opera that featured a man on film experiencing a Black Lodge moment, ala David Lynch’s “Twin Peaks”. The event, held in the Philadelphia Film Center, combined a film with a live musical performance provided by an industrial, gothic rock band, Timur and the Dime Museum, and a string quartet from the Philadelphia Orchestra, plus some electronic sounds. This production pushed right past the boundaries of both classic and most contemporary opera and invaded rock’s territory. At one point late in the performance, I shared the sentiment of The Man on the screen; I just wanted to get out of there. It might have gone better if I had prepared. Honestly, this was a performance that I liked more after reading about it following the performance than I did during the performance. Let me try to make sense of that; I will avoid the philosophical aspects of that assessment, i.e., would it really be better for me as a person having an encounter with art to prepare. Regardless, I totally support its inclusion in OP’s Festival O22 this year. Looking for boundaries, you must go past where they are, a technique known as successive approximations.

Image from Black Lodge film with Timur on screen and with performers in front of screen, including Timur and the Dime Museum and the Opera Philadelphia String Quartet. Photo by Steven Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

What was going on in the film is not entirely defined, I think. In fact, the music by David T. Little and libretto by poet Anne Waldman were written before Director Michael McQuilken developed the stage play. Director Michael McQuilken reported, “So my task was three-fold: invent a narrative, invent an emotional arc for the lead character(s), and attach all of it to preexisting music (emotions) and lyrics (images and ideas). A deeply complex puzzle.” Mr. McQuilken describes the plot as: “Trapped in a nightmarish Bardo, a place between death and rebirth, a tormented writer..faces down demons of his own making. Forced to confront his darkest moment in his life, he mines fractured and repressed memories for a way out.” Okay, that helps. He continues: “The woman…is at the center of all the writer’s afterlife encounters. She is the center of his life’s greatest regret, and she materializes everywhere in this Otherworld.” Okay, that helps a lot. In the film, the man accidentally shoots the woman. It turns out that an inspiration for the film’s screenplay was William S. Burroughs, an influential American writer and visual artist who was revered by American subcultures rebelling against majority values, such as punk rockers. Reportedly, Mr. Burroughs was a drug addict and was haunted by a seminal event in his life: he accidentally shot and killed his second wife. Now the film makes even more sense.

Jennifer Harrison Newman as The Woman. Photo by Steven Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

The libretto was fragmented speech, sort of a stream of semi-conscious approach, and perhaps offered too much of that. To get it all, I had to read the subtitles on small screens on either side of the theater (the font size made me realize that it’s time to change my glasses). There seemed to be several key phrases: his desire to get out of there; the man was trying to write his way out of there; and he issued this warning to all, “Be careful what you need to know”. The visuals ranged from an empty warehouse room to a bar to the desert to The Woman covering the Man with goop and then inserting tubes into the goop all the way into the man. It’s a lot to make sense of if you only have a vague sense of what is going on.

Two images featuring Timur as The Man. Photos by Steven Pisano; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

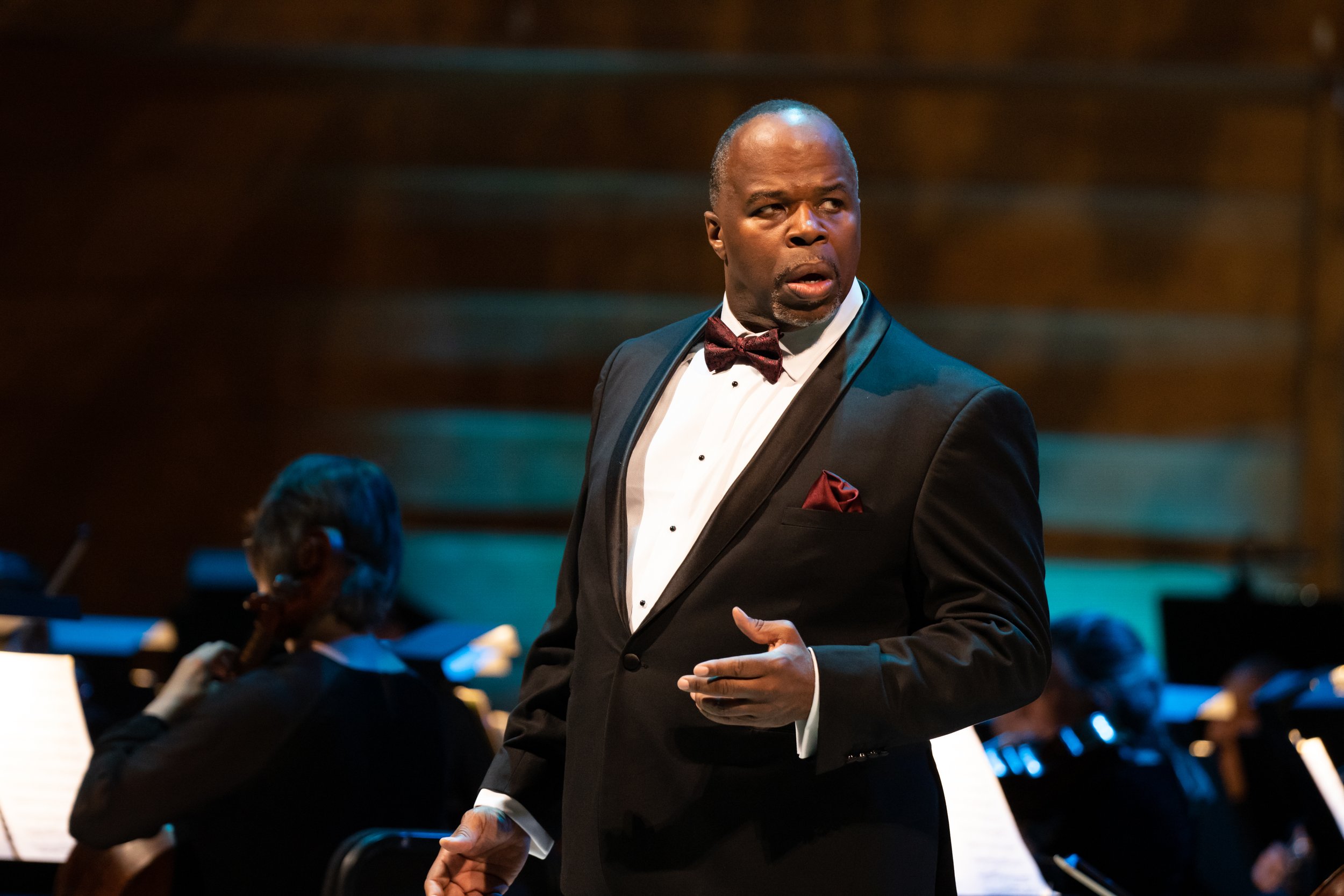

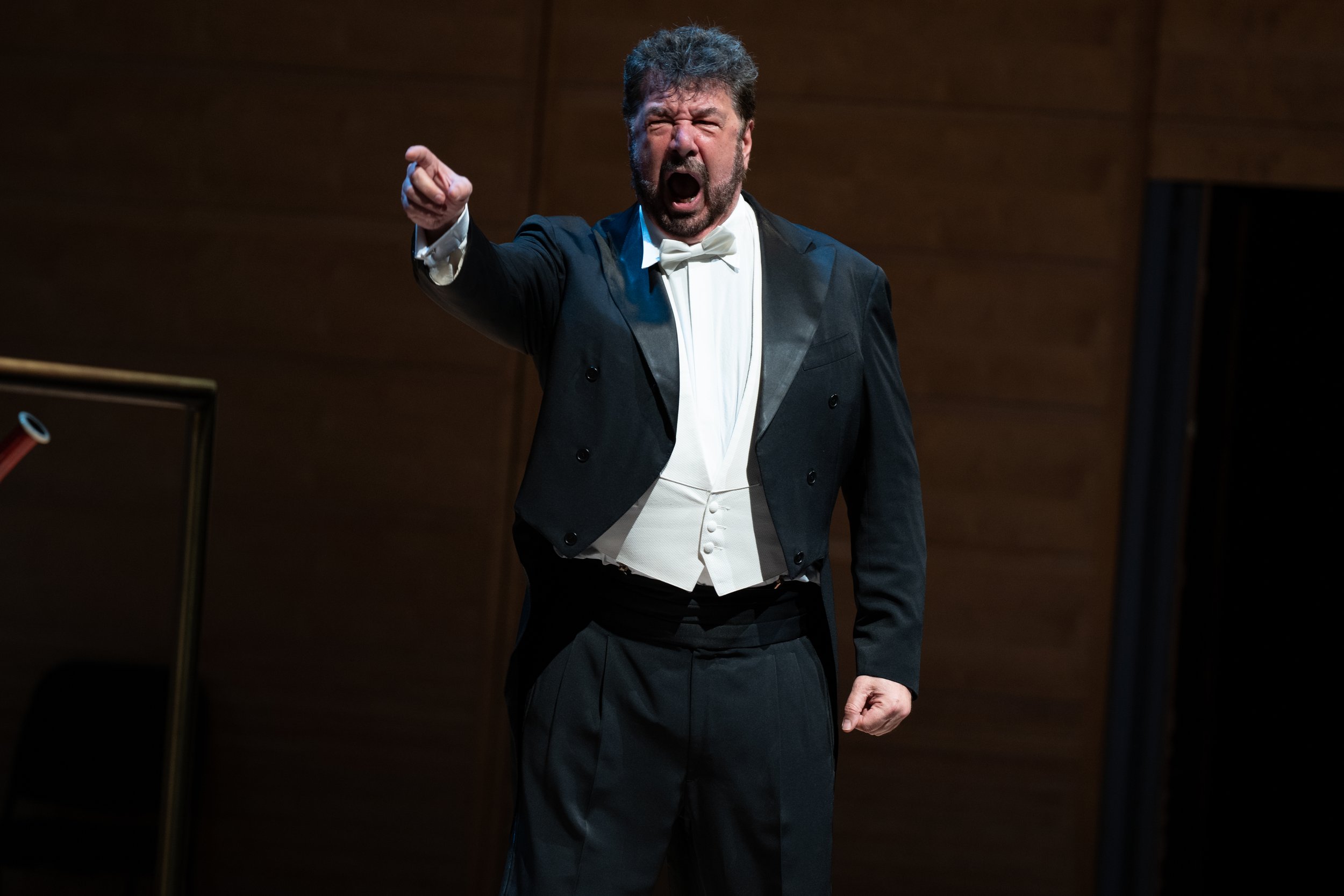

I liked the music, maybe my first rock opera. I accepted the ear plugs offered at check in but didn’t need them - okay for me in the back, but I noticed that the members of the string quartet on stage appeared to be wearing noise cancelling headphones. I am not familiar with industrial rock but have a vague idea of gothic rock. The lead singer was made up to look gothic. The internet says industrial rock is a fusion genre combining industrial music and rock music. Again, from the internet, “industrial music is a genre of music that draws on harsh, mechanical, transgressive or provocative sounds and themes.” Now you know as much as I know, but I do give opera omposer David T. Little credit for boldness in adventuring into industrial rock. The string quartet ( Luigi Mazzocchi, Elizabeth Kaderabek, Yoshihiko Nakano, and Jennie Lorenzo) played well when I could hear them. I think the Dime Museum band (Hannah Dexter, Andrew Lessman, Matthew Setzer, and Milo Talwani) did an excellent job producing an appropriate sound; can rock music be brooding? There were a few brief solo riffs from the band; I would have enjoyed even more. Singer Timur had an impressive vocal range, tenor, baritone, and gothic rocker who I thought did a great job; perhaps there was some opera technique in there somewhere. Timur also played The Man in the film to great effect. The Woman, dancer Jennifer Harrison Newman, was captivating in the many strange situations in which she was placed. Place my misgivings in context: at the conclusion of the performance, the performers received an enthusiastic ovation.

In conclusion, if you have the opportunity to attend The Raven featuring an interactive pre-performance, by all means choose to participate; both activities will enhance your engagement with Poe’s “The Raven”. If you have the opportunity to attend OP’s Black Lodge, I think your experience will be more complete and at least a little less baffling if you prepare; see The Fan Experience section below for an upcoming opportunity to view it. I think both of these events were essential elements of Festival O22 as measures to exploare the boundaries of opera. Also, I like opera fusion efforts, and there are some excellent jazz opera and blues opera fusions out there today. My hope is that OP will continue to commission such efforts, though maybe put a little more opera in the rock opera ones. In my comments reporting on Festival O17, I stated: “The brightest star in the U.S. opera universe this season is not in New York, but in Philadelphia. Opera Philadelphia is bringing excitement and modern relevance to opera this year, in bucket loads”. This year in O22, Opera Philadelphia restarted the bucket line. Welcome back!

The Fan Experience: The Raven was performed on September 21, 24, 29, and October 1 in the Miller Theatre. Black Lodge was performed on October 1 and 2 in the Philadelphia Film Center. (Note: Beginning October 21, screening of Black Lodge will be available on the Opera Philadelphia Channel.

The two-week Festival O22 featured 42 events. This is an annual festival that was in hiatus for the last two years due to the pandemic. For O22, COVID-vaccinations and masking were strongly encouraged but not required; let’s pray that for O23 they need not even be a consideration. OperaGene’s three previous blog reports covered events at O22:

Festival O22’s Opera on Film Fits Right In: Comments on Like, Share, Follow

Opera Philadelphia’s Opera on Film: Art and Social Issues Night

Opera Philadelphia’s The Copper Queen and Otello: A Day at the Opera Festival

Some advice for next year: Be smart; get on OP’s email list to learn about O23 as soon as possible – at the bottom of their website page, you can enter your email address to receive notices from them. Then will come the hard part – prioritizing which performances to see during a two-week period. For Festival O22, OP offered 12 film events, three staged productions with multiple performances, concerts, and evening affairs. There were both matinees and evening performances. You will have your work cut out for you in deciding. My wife and I have attended all the fall festivals so far, since 2017, and each has been a highlight of our year.