New opera has its own special excitement; it's fresh and speaks more directly to our time. More new operas are appearing now, and the Washington National Opera brings an American brand of that excitement to the Kennedy Center through its American Opera Initiative. Each year, one 1-hr and three 20-min new operas are premiered. The 1-hr opera was presented on Friday night and Sunday afternoon, while there were two presentations of the three short operas as a group on Saturday night. The AOI focus is on American opera, not so much by the stories themselves which are universal, but through the opera’s creators, American composers and librettists, primarily giving creative opportunities to new and unproven talents. The critical importance of the program was made clear by well-known librettist and a mentor for the AOI program, Mark Campbell, who stated that how to write opera is not taught in colleges or music conservatories. Kudos to AOI and its director, Robert Ainsley for helping to fill that void.

Proving Up by Missy Mazzoli and Royce Vavrek, 1-hr

l to r: Allegra De Vita, Madison Leonard, Alan Naylor, Christopher Kenney, Leah Hawkins, and Arnold Livingston Geis. Photo by Scott Suchman; courtesy of Washington National Opera.

I have trouble with this one. Everything about it was exciting. It was this year’s one-hour opera premiere. This composer/librettist team of Missy Mazzoli and Royce Vavrek were already successful; their opera last year, Breaking the Waves, won rave reviews and awards, probably my favorite opera of last year. The cast of Domingo-Cafritz Young Artists are opera stars in training. My anticipation was high. Yet, as I watched and listened, I disliked this one, and still do, but the truth of it keeps smacking me in the face; it haunts me. This opera is about gambling on the American Dream and losing, the American Dream as a suicide mission, not because it’s believers didn’t work hard enough, but because the odds of success were against them. Sending soldiers into battle, success is not assurred and you know you some will not survive; the same was true of settlers in Nebraska, attempting to take advantage of the Homestead Act in the 1870s. It wasn’t complicated to “prove up” to the requirements of the Act - settle on a parcel of land, build an adobe hut, bring in five harvests, exhibit acres of waving grain, and have a glass window in your hut…the deed to the property is won. However, many of the settlers started with almost nothing, depending on every harvest. The Karen Russell short story (from her book “Vampires in the Lemon Grove”) on which the opera is based involves neighbors attempting to pass around a window, scarce and expensive, to fool inspectors and get their deeds. Some managed to succeed; this is not their story. This is the other story, the Greek Tragedy one. For some, it was just bleak, impoverished failure marked by poverty, hunger, disillusionment, and death after wanting it so much and trying so hard, even compromising morals, as the rains did not come, but the insects did, and family members wore down and died from starvation, disease, accidents, and the harsh conditions. What haunts me? It has raised the question in my mind of “Is it happening now” to some in pursuit of the American Dream, maybe not death by starvation, but by spirits broken against insurmountable odds? And do we care? A certain American leader said that he likes heroes who didn’t get captured. Is that the American spirit today - be a winner and losers are just collateral damage?

Christopher Kenney as Pa Zegner and Leah Hawkins as Ma Zegner. Photo by Scott Suchman; courtesy of Washington National Opera.

Details? The set was minimal and bleak, conveying the theme. The opera involves a family of six and a character known as The Sodbuster. It involves the supernatural and is difficult to follow. It’s not clear whether The Sodbuster is real or a demon. Initially, I delighted in the two young daughters played spot on with the charm of youth by Allegra De Vita and Madison Leonard, until they sang about the hardships the family had endured including “two dead daughters”. Uh oh, very cute versions of Marley’s ghost I surmised, until their teasing became sinister and unsettling. Their voices were perfectly paired to sing their duets. Having seen them perform locally as young sopranos, it was fun to see these two convincingly portray children. Another highlight for me was Leah Hawkins who played the mother with a powerful voice imbued with emotional sensitivity and with an awareness of the impending doom. Her aria about what she would never hate was probably the only warm tug on my heartstrings. The father was played effectively by baritone Christopher Kenney, but the role seemed a little off. A man beaten down, he had turned to drink; where did the alcohol come from? At least we should have seen him staring despairingly at an empty flask. Milo, the young, impetuous son entrusted with too much responsibility was played convincingly by tenor Arnold Livingston Geis, and his distraught, defeated brother Peter, who had no vocals, was portrayed effectively by actor Alan Naylor. Timothy Bruno’s The Sodbuster lifted the bad dream all the way into the nightmare category; his imposing size and impressive base voice were perfect for his role as abstract unrelenting opposition. Tim, if they ever make an opera of Nightmare on Elm Street, you must audition. At the same time, The Sodbuster role seemed disproportionately large and might have been even more effective if trimmed back a bit.

Alegra De Vita and Madison Leonard as the dead Zegner sisters, and Arnold Livingston Geis as son, Miles Zegner. Photos by Scott Suchman; courtesy of Washington National Opera.

Ms. Mazzoli’s music is designed to fit the characters, circumstances, and the theme and is elegantly effective for that. She is unusually inventive in creating and employing new sounds to color the story, such as using acoustic guitars being struck not strummed to create an effect she wanted associated with the family. The orchestra conducted by Christopher Rountree was chamber size at 14 pieces and accompanied all four operas, although the conductor changed for the shorter versions. With the constraints on orchestration and set design, the words become the focus, and I felt that I was experiencing opera as poetry, rather than as straight-forward narrative, with staging and music enhancing the imagery and emotion. Richard Wagner called some of his works “music dramas”; this was a “music poem”.

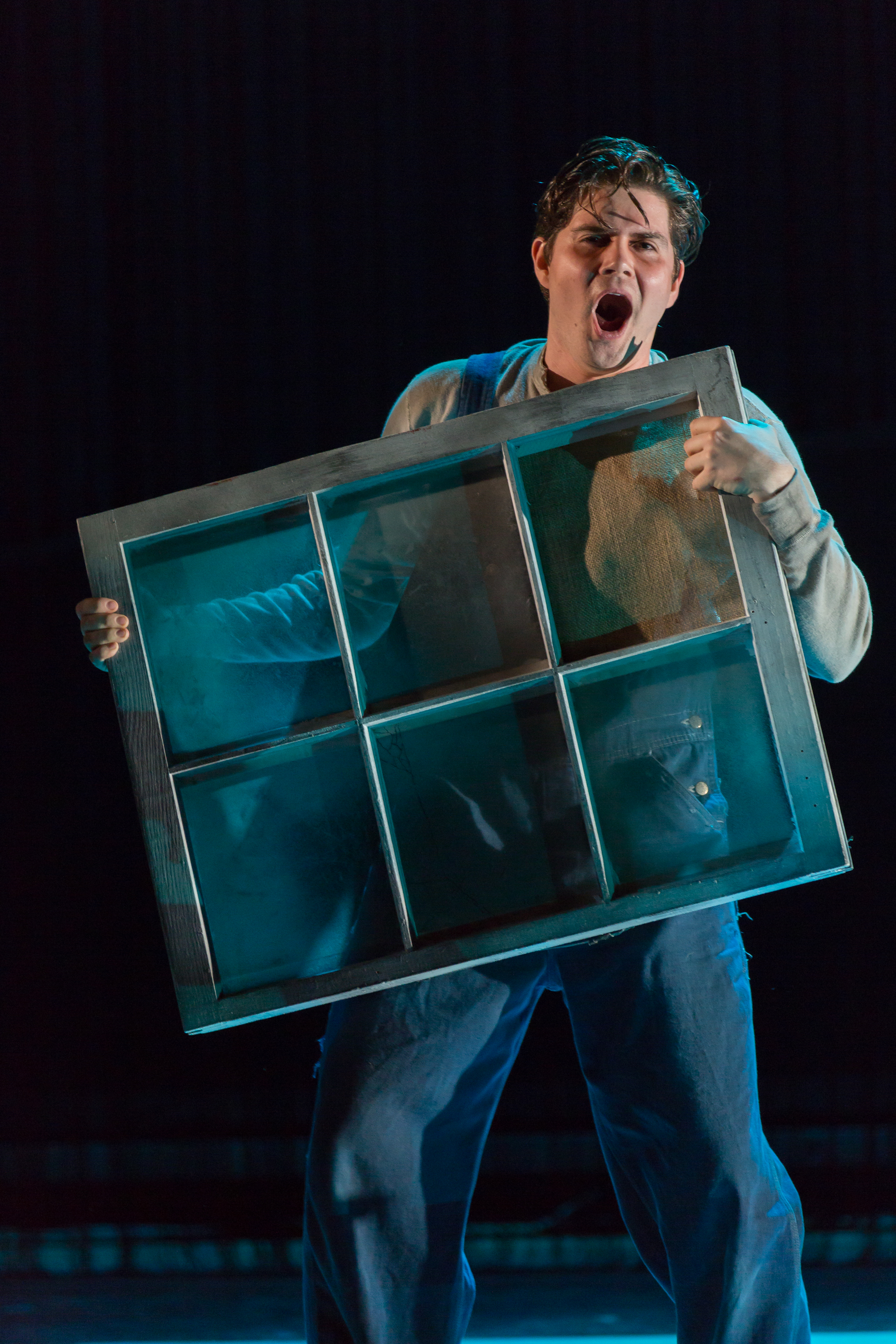

Timothy Bruno as The Sodbuster. Photo by Scott Suchman; courtesy of Washington National Opera.

I said I dislike this opera, and I do, immensely. Am I glad I saw it? Yep. Would I attend another performance? Yep. In fact, the opera’s commission was supported not only by AOI, but by Opera Omaha and the Miller Theater of Columbia University and Proving Up will now receive new productions in those locations, and were I there, I’d attend at least one of them, maybe both. Go figure.

A Bridge for Three by Nathan Fletcher and Megan Cohen, 20-min

Three characters from different time periods stand on the Brooklyn Bridge about to jump: Jimmy James (tenor Alexander McKissick), to test his artificial wings; Molly (mezzo-soprano Eliza Bonet) over a failed relationship, and Roland Archister (baritone Michael Hewitt), a Wall Streeter in the stock market collapse of 1929. Each jumps and expresses their varying reactions as they fall; love of life is affirmed for some, but not all. I especially enjoyed Mr. Fletcher’s music, which included a few jazz riffs. All three 20-min operas are presented as concert versions (without sets) with George Manahan conducting, and this one qualifies as a music poem.

Fault Lines by Gity Razaz and Sara Cooper, 20-min

A father (played by baritone Michael Hewitt) sexually abuses his Japanese maid (played by soprano Laura Choi Stuart) during the time of WWII; she complies to save her job and avoid being sent to a California internment camp, and she faces the wrath of the wife (played by mezzo-soprano Eliza Bonet). Later, a struggle ensues with the son (played by tenor Alexander McKissick) mortally wounding the maid. This is a powerful vignette of racism and sexism made especially poignant by the internal struggle of the mother as she accepts her maid’s revelation she has been raped, but then chooses to protect her family over justice when the maid is killed, repeating the line “…we are good people, and we do what we must do.” Indeed, what ills we good people will allow. This opera was more drama than poetry which could justify a larger staging; it packed a lot into 20-min.

Precita Park by John Glover and Erin Bregman, 20-min

A family of five move into their new residence, a small shack in Precita Park, following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. While Lilah (played by soprano Alexandria Shiner) mourns that loss of someone close, she suffers the bickering of her siblings, contrasting comedy with pathos. The siblings were played by soprano Laura Choi Stuart, mezzo-soprano Eliza Bonet, tenor Frederick Ballentine, and baritone Michael Hewitt. For me, the comic elements were subdued somewhat by having witnessed the trauma of the previous two performances. This one was also a music poem. Probably the best short operas will be.

I greatly enjoyed the singing and performances by all the Domingo-Cafritiz Young Artists in all three operas. Brava, bravo, bravi!

Note to composers and librettists: It would be ok with me to insert a few longer arias with great melodies into new opera, something I would find myself humming on the way home and maybe try to find on iTunes to hear again. Really, I’m ok with music written just to sound good as well as support the libretto. I love the new opera you create; it’s just a small wish.

The Fan Experience:

Talk backs were held for thirty minutes after Proving Up and after the three shorter pieces. All composers and librettists were in attendance for their respective talk backs, as well as the AOI director. It was especially interesting to hear them describe how their working relationships had developed. I strongly recommend these after-performance talks at the Kennedy Center.

At the Proving Up talk back were AOI director Robert Ainsley, librettist Royce Vavrek, composer Missy Mazzoli, and writer Karen Russell. Photo by author.

To beat commuting stress, I headed to the 9 pm performance on Saturday early. I arrived a block away from the Kennedy Center North B entrance at about 8:15. Earlier KC performance crowds were emptying from the parking decks and it took 25 min to go the last block. While waiting, I remembered I had forgotten my ticket. Here the good begins. When I finally got to the gate I was waved in for free to move the traffic along. I went to the purchase ticket booth and show them my ticket email on my iPhone; thank you iCloud, though I suspect they could have managed with my name and phone number. They printed a ticket for me and I arrived at my seat with ten minutes to go, richer for the experience. As always for DC, I advise allowing more time than you think you will need.