The answer is one princess because it is a theater problem, not a math problem, but we will get to that in a minute. One of the joys of Opera Philadelphia’s season-opening festivals each Fall is getting to see works that are either new or not often performed in the US. OP’s production of The Love of Three Oranges (1921) by Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) fits in the not often performed in the US category. The opera is, however, quite popular in Europe where it is often staged as a children’s opera. But Friday night in the Academy of Music, it brought madcap zaniness and eruptions of laughter to a largely adult audience that went home as happy as a child.

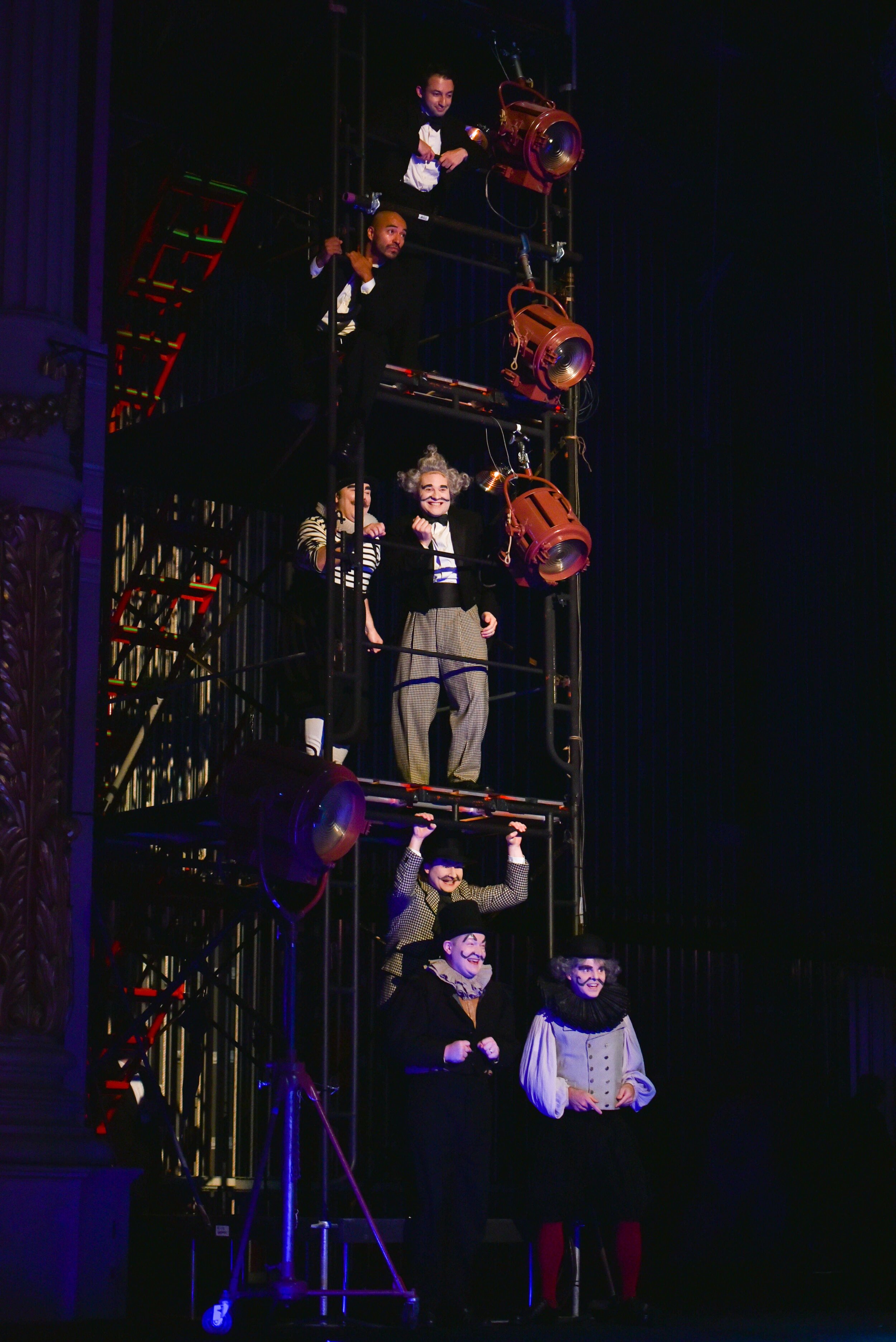

The Eccentrics announce The Love of Three Oranges will be performed. Photo by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

I think three intertwining elements are at work to make Oranges a success. First is that we all love fairy tales, the fanciful way we connect with truths about human nature; second, humans seem to innately love to play the fool or laugh at others playing the fool (we are especially amused when we realize that there is a method to the fool’s madness); and finally, the composer and thus, the music, is world class. The Russian composer Prokofiev wrote only one other opera well known worldwide, War and Peace, but he is renown for his ballets such as Romeo and Juliet and Cinderella, and many orchestral works, especially Peter and the Wolf. He wrote the libretto for Oranges with Vera Janacopoulos, based on Vsevolod Meyerhold’s adaptation of seventeenth century playwright Carlo Gozzi’s fiaba. Gozzi’s play used stock commedia dell’arte costumes for different character types and several of these are used in OP’s staging. OP’s productions uses the English adaptation by David Lloyd-Jones, interesting since Prokofiev wrote the libretto in French because he thought Americans would eschew Russian, but I would add important, since the opera moves at a pace that would make keeping up with subtitles taxing, especially since much of the fun is in the visuals.

The King of Clubs played by Scott Conner seeks medical advice for his son. Photo by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

The Eccentrics keep watch and react to the tale’s twists and turns. Photo by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Partly, The Love of Three Oranges is the result of Prokofiev’s determination to be original, to refuse to accept the restrictions of current conventions. He had the talent to write the sort of works that were in vogue, but not the inclination. In Oranges, he not only eschews opera conventions, but literary as well, most notably by “breaking the fourth wall” (stages have three walls; the fourth wall is the invisible barrier between the performers and the audience; if a performer directly addresses the audience or comments on the play itself, the fourth wall is broken). Four groups of characters appear on the stage before the story appears. Each group expresses their preference for the type of story to be presented: tragedy, comedy, romance, and farce. They were followed by a group called the Eccentrics who announced the story and expressed the desire that all watch until the end. The Eccentrics broke the fourth wall at least twice by interfering in the story’s direction. All the groups entered makeshift stands on each side of the stage to react to the parts of the story they liked. A prince is unhappy, bedridden with depression and potentially fatal hypochondria. His father, the King of Clubs is worried who will inherit the reign. Plots by family and court members abound to wrest power away from the Prince. Grand attempts to make the Prince laugh fail, until the person least likely to make him laugh does. For laughing, he is cursed to be obsessively in love with three oranges, and he leaves on a quest to find them. The three small oranges he finds grow into three very large oranges, each containing a princess. He falls in love with the last one opened. I was going to tell you how two oranges were subtracted, but it’s too sad – it’s theater and it had to be done. Anyway, the dark forces try to interfere, but all ends happily. Along the way we are entertained by one over the top character after another. Director Alessandro Talevi had his hands full. I really liked his synopsis of the meaning of the quest myth printed in the program book: “…only through contact with new, often seemingly dangerous forces, can an individual experience personal growth or maturation.” He strove to bring forward this message in the mayhem; he even uses references to known personages and partly a wild west setting to do so. Kudos to him.

left photo: The Prince played by Jonathan Johnson is not amused by Truffaldino’s antics, played by Barry Banks. right photo: The evit witch Fata Morgana played by Wendy Bryn Harmer seeks to keep the Prince from laughing. Photos by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Commenting on the singing for this opera is difficult because there are so many singers and because of the nature of the music. There are sixteen singers named in the program book even without listing the singers in the groups that Prokofiev thought of as the Greek Chorus, whose job is to sing, but also comment on the action; kudos to Chorus Master Elizabeth Braden. The entire cast gave an excellent performance. My favorite was bass Zachary James who played the funky chicken with the feline personality, alias The Cook, the possessive and dangerous holder of the three oranges. Tenor Jonathan Johnson as the Prince gave us all one of the best laughs of the night with his operatic approach to laughter. Soprano Wendy Bryn Harmer gave us a fierce evil witch Fata Morgana, and tenor Barry Banks as Truffaldino provided much of the energy in his scenes. The whole affair was anchored by an authoritative King of Clubs played by bass Scott Conner. Each member of a large cast had their moments. The costumes (Manuel Pedretti), scenic design (Justin Arienti), action design (Ran Arthur Braun), and lighting design (Giuseppe Calabro) were all excellent and contributed to the fun.

The Prince (Jonathan Johnson), Farfarello (Ben Wager), and Truffaldino (Barry Banks) begin their quest to find three oranges. Photos by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Oranges is through composed by Prokofiev. I’d have to hear it again to know if any themes were repeated. The action on stage and the music were intimately involved; every movement on stage and every mood change in the story were responded to or anticipated by the music. I like it for that reason. The music is melodic and harmonious and to be enjoyed on that basis, but in relatively short discontinuous segments. It can be tender, raucous, foreboding, whatever is required, in fast succession. Kudos to Conductor Corrado Rovaris for bringing this music to life and for deft coordination with the action on stage. Mr. Rovaris was also instrumental in getting this opera onto the O19 program. The singing is almost completely recitative to tell the story. A famous march theme in the opera offered one of the few extended melodies. The music is so good it can’t be discounted, but it is so integral to the opera that I doubt you will want to play it at home. Prokofiev did compose The Love for Three Oranges suite abstracted from the opera that is pleasant enough and worth a listen.

The Cook played by Zachary James sings softly but carries a big ladle. Photos by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

In most fairy tales, the elements of the story and staging are there to sugarcoat the underlying moral of the story. For Oranges, the moral of the story provides the engine to which the gags are hooked onto. You can dig more deeply into it; it is claimed to be satirical, but if so, it satirizes everyone. I prefer to believe Prokofiev’s intent, as he himself was quoted as saying, was for us to enjoy each train car filled with visual and audio fun as the little engine of the story pulls it past us. All seriousness aside seems to be the point of his opera.

The three oranges, once secured by the Prince (Jonathan Johnson) and Truffaldino (Barry Banks), have grown. Photos by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

I think how you approach this production will affect your response to it. My wife who loves fairy tales was into it immediately. I didn’t really start laughing until the Prince did. I think base-baritone Zach Altman who played prime minister Leander offered a good approach with a comment in the OP study guide, “Don’t try to get the whole experience in one try. Just let it wash over you.” In fact, if I lived in Philadelphia, I’d take it in again.

The heart of the Princes (Jonathan Johnson) is captured by Princess Ninetta played by Tiffany Townsend. Photos by Kelly & Massa; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Festival O19 and its two predecessors are seeking to push opera towards its edges and find what it can be. Sergei Prokofiev was doing the same thing. It’s a good fit.

The Fan Experience: Festival O19, five different productions over twelve days, continues through September 29; performances of The Love of Three Oranges continue through September 29 and tickets are available. Check their website carefully for What’s On; the performances are often accompanied by special events, lectures and meetings with those involved. One of the special events not to miss is the pre-opera talks occurring one hour prior to performances that provide a excellent orientations to the performances. The Academy of Music is modest in size for a major opera house, which means all the seats are relatively close to the stage, but I recommend checking with guest services at 215-732-8400 on seat selection for best viewing.

This report is part II; my part I blog post preceded this one. I have two more events on my schedule for reports.

Philadelphia is a great city to visit for food, historical sights, and the arts.