Opera Philadelphia recently added a film version of composer Jon Deak’s The Passion of Scrooge (2018) to its streaming Channel lineup for the holiday season. Combining opera and Scrooge, how could I resist? This filmed version of Mr. Deak’s composition, with libretto by Isaiah Sheffer and Mr. Deak, has the Dickens’ story bound in the composer’s personal life journey. I caution you not to compare this production to your favorite version of A Christmas Carol; it will most likely lose a battle with the film or stage production that impacted you the most (for me, it is a tie between Reginald Owens from 1938 and Alistair Sim from 1951). While I had a few tears in my eyes near the end, I enjoyed this performance more as one might a new Christmas toy, something fresh and colorful with movement, sounds, and surprises…and more. Accepted on its own terms, it is a wonderful Christmas time treat!

The score and libretto of The Passion of Scrooge were created over a ten-year period (1986-1996) at a time when the composer was having personal and family problems, a self-confessed time of great difficulty and much introspection for him. He poses the question in this production of what is the story behind a composer’s work? His thoughts came to focus on how remarkable it was that Scrooge had within himself the power of redemption, to see the error of his ways and to change, to make the business of life less about earning money and more about compassion, helping others, and love, the message from A Christmas Carol that transcends religious boundaries (his co-librettist is Jewish). The film opens with Mr. Deak in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, where he engages Shakespeare’s the “Seven Stages of Man” before making the short walk to St. Mark’s Episcopal Church where the chamber opera, a partially staged, concert version is to be performed without costumes or sets. As he walks along, he mulls Marley’s admonitions to Scrooge, and on seeing holiday street scenes, he is reconnected with thoughts of children at Christmas. Engaging children in composing music is a special interest of composer Deak’s.

Movie frame from The Passion of Scrooge with multiple image overlays. Photo by H. Paul Moon; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

The drama that unfolds in the church has perhaps most aptly been compared to a radio drama, complete with music and sound effects, such that imagination provides the details of the story. The story is marvelously told by baritone William Sharpe through both narration and acting, sometimes sung and sometimes with dialog. The vocals are entirely recitatives, faithfully relating Mr. Dicken’s tale. Mr. Sharpe is a fine singer with extraordinary story telling skills; he seemed a natural for the part. Composer Deak chose to use just one singer because he felt that all the characters come out of Scrooge’s head. However, in the telling of this story, the instruments and their players also play parts, adding dialog and color using their instruments in response to Mr. Sharpe’s revelations portraying Scrooge and the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future. In this production the musicians also engage in a bit of choral singing, making of ghostly sounds, and uttering of a few “bah humbugs”. It is very clever and amusing and fun. Listening to the audio alone the film reminded me somehow of the beloved Camille Saint-Saëns Carnival of the Animals when done with narration; thus, this report’s name, the ‘Carnival of the Instrumentalists’, said with great affection for Mr. Deak’s music drama. For me, the delight of watching and responding to the interplay between the story and the music and the musicians is a trade off with the drama’s impact, but it is what makes this performance compelling viewing. Heard over the radio, the drama might reign.

Baritone William Sharpe as Scrooge. Photo by H. Paul Moon; courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Composer Deak’s music is pleasing and inventive and constitutes a lesson in how instruments and music can engage in storytelling. Listening to the music is a pleasure for the ears and the emotions. Much of the music has the rhythm of speech, using composer Deak’s technique known as “Sprechspiel” or “Speech playing”. The musicians are members of the 21st Century Consort, a group dedicated to playing contemporary music. They were led in this performance by Conductor Christopher Kendall who clearly faced a huge challenge in coordinating the timing with so many stops and starts and changes, interspersed with critically timed sound effects. This was a highly talented group of performers who carried off the production flawlessly (with the advantage of film editing, of course). The members of the Consort, seated in a circle, included:

Richard Barber, Contrabass

Paul Cigan, Clarinet

Daniel Foster, viola

Lee Hinkle, percussion

James Nickel, French Horn

Alexandra Osborne, violin

Susan Robinson, harp

Boyd Sarratt, add’l percussion

Sara Stern, Flute

Jane Steward, violin

Rachel Young, cello

Lisa Emenheiser – piano, prologue improvisations and end credits

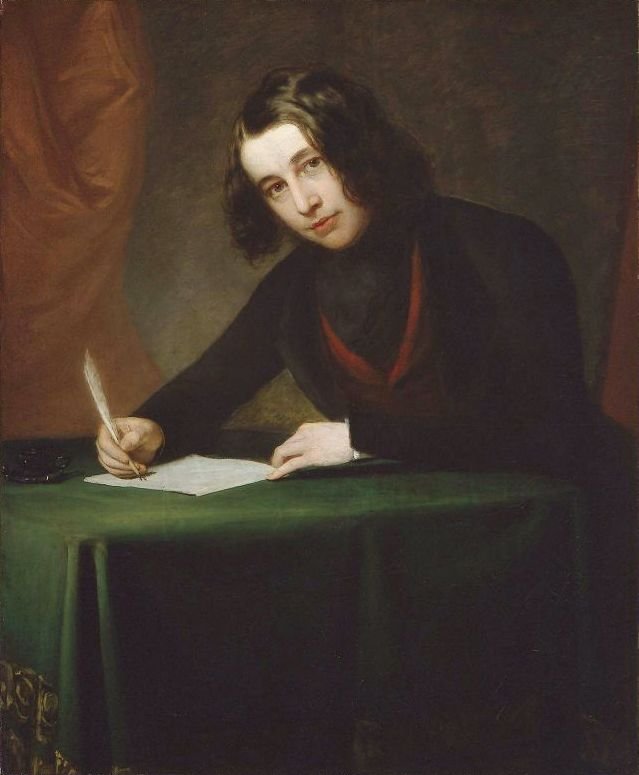

left: Image of composer Jon Deak in The Passion of Scrooge; image by H. Paul Moon and courtesy of Opera Philadelphia. right: 1842 Painting of Charles Dickens by Francis Alexander; image in public domain on Wikipedia.

The performance includes two acts. The interlude in between the acts features the composer taking the subway and walking the streets of New York City into Times Square. The camera pans some of the street people making the point that even today the poor need our help. The photography, direction, and film editing was done by H.Paul Moon; kudos to him for an excellent job. He used a “floating camera” technique with constantly moving and rotating views of the performers. Scenes from an early film titled Scrooge (1935) are effectively intermeshed onto the filmed performance during many of the scenes, triggering memories for me of past viewings, as though ghosts of Christmases past.

Like A Christmas Carol, The Passion of Scrooge ends on a note of hope (“the shadows of things that would be may be dispelled”) and a strong appeal to the human spirit (“there is time, there’s still time”). As these phrases and others from the drama resonate through our heads as they do Scrooge’s; we all are brought face to face with the redemptive power of love, and its inclusiveness is proclaimed with Tiny Tim’s “God bless us, everyone”.

The Fan Experience: The Passion of Scrooge is available on demand to Opera Philadelphia Channel subscribers only, now until January 8, 2023. Annual subscriptions are available for $99, monthly for $9.99 and can be cancelled at any time. For more insights into the film, check out the YouTube video, “The Making of “The Passion of Scrooge””.

Most of the videos on the Channel, but not this one, are available for individual purchase. However, you can cancel your subscription after one month at a total cost of $9.99 and have access to this video and the others on the Channel for the entire month. Frank Luzi, Vice President of Marketing Communications & Digital Strategy Executive Producer, explained that The Passion of Scrooge is one of a series of “programs produced by other artists and companies under the banner of ‘Opera Philadelphia Channel presents’, and these are meant to come to the channel in limited runs and available only to subscribers.” Here is a link that lists some of the upcoming additions in this category; I look forward to the upcoming screening of Hansel and Gretel.

The Passion of Scrooge is available for renting or buying from several other streaming services as well. Subscribers to the Channel have 24/7 access to a variety of content, including videos of Opera Philadelphia classic opera performances and new, imaginative content. Check my report on the Channel’s 2021-2022 season.