I attended last Saturday night’s opening of Dead Man Walking (2000) produced by Washington National Opera at the Kennedy Center. I am not over it yet. I had not read the book, nor seen the movie by the same name (the complete name of the 1993 book is “Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States”). I have WNO season tickets and Walking was simply next on the agenda. I approached this opera with both a little anxiety and a little dread: first, it is a modern opera by composer Jake Heggie and librettist Terence McNally and, while I like going to new operas, I often find the music in modern operas to be …well, challenging. Fortunately, Anne Midgette’s preview in the Washington Post had assured me the music was “tonal” and “melodic”; it was also reassuring that it has received fifty performances since its premiere. My second concern was that what I knew of the story made it sound depressing, not the way I might want to spend my Saturday evening.

If you plan to attend the opera, see the movie, or read the book, be forewarned that this blog report will talk about the ending of this true story, which is the same in all three sources. I felt I had to watch the movie after seeing the opera to compare the two methods of storytelling. I still have not read the book, and am in a tug of war with my feelings about whether I want to or not. I think the charge that these three treatments of the story are depressing is fair, until you have managed to get through the entire story with one of them, and then, they are more than that, much more. The story itself is an exploration of being human and being forced to confront violence and its aftermath. I can vouch that the movie and the opera do this well.

Kate Lindsey as Sister Helen Prejean and Michael Mayes as Joseph De Rocher. Photo by Scott Suchman and courtesy of Washington National Opera.

Briefly, Joseph De Rocher (name used in the opera version), a young man who had grown up in a poor family in Louisiana, had with another young man come upon a teenage girlfriend and boyfriend parked in the woods. De Rocher and his accomplice brutalized the couple, raped the girl, and killed both her and the boy. The accomplice had a better lawyer and got life imprisonment for his sentence. De Rocher had not faired so well and was on death row when he contacted Sister Helen Prejean. He asked for her help in getting his sentence reduced; he maintains his innocence, claiming it was the accomplice who had killed the couple. Sister Prejean eventually agrees to become his spiritual advisor and takes on the goal of trying to get De Rocher to accept the responsibility for what he had done. He admits his guilt immediately before he is put to death by lethal injection. More than grappling with our opinion about the death penalty, we are left grappling with our feelings about this young murderer. Have we or can we forgive this repentant young man who committed such a heinous crime, as Sister Prejean was able to do? Once a crime has been committed, should our goal be revenge and punishment or forgiveness and redemption? Would we be willing to flip the switch that puts him to death?

There were three special guests for Saturday night’s performance, the composer Heggie, the librettist McNally, and the author, Sister Prejean. Sister Prejean also attended the brief post opera wrap up session. In response to a question about her view of the opera, she said that opera was the fullest or most complete art form. There is no question in my mind that this story is opera worthy. Books and movies have their own advantages, but at its best, opera with its deployment of the human voice conveys feeling, emotion, and human values in ways and to a degree that books and movies do not. Admittedly, I am prejudiced, but I liked the opera’s telling better than the movie.

WNO’s staging of the opera began with a powerful depiction of the rape and murders. The movie sustained suspense by not completely revealing De Rocher’s guilt until the end. However, being confronted immediately with the brutality and savagery of De Rocher’s act made forgiving him seem impossible and leaves the audience in that quandary throughout. Unfortunately, I found the rest of the staging less than desirable, such as having Sister Prejean sit in a chair to simulate driving to the prison. Aspects of the staging were creative and added to the impact, such as having the young victims run across the back of the stage while De Rocher is dreaming about that night. I realize that opera always asks the audience to immerse itself in the fantasy, but for most of the evening, I could not help but wonder if Walking had been given a small budget for staging; the visual pleasure of opera is important. The final scene was detailed and compelling. Much has been made in reviews about the ending because the gurney’s arm sections supporting De Rocher gives the support a cross-like appearance, and some people feel that it is portraying a crucifixion-like setting where the De Rocher is depicted as dying for our sins. Sister Prejean explained that the shape of the gurney used in the opera is as it was at the actual scene. However, in the opera ending, the gurney is raised to fully face the audience. If this was meant to be an effective statement against capital punishment, I did not find it so. I was still struggling with how could I forgive this man.

Susan Graham as De Rocher's mother. Photo by Scott Suchman and courtesy of Washington National Opera.

Baritone Michael Mayes plays De Rocher and has played this role many times before; he has it finely honed, in acting and singing. I thought mezzzo-soprano Kate Lindsey who plays Prejean was excellent, but at the same time, her performance both singing and acting did not stand out as much as I had expected. Perhaps, she will grow stronger in later performances as her confidence grows, allowing her to better employ her obvious talents. Clearly, the person on stage who stood out was international opera star, Susan Graham, who plays De Rocher’s mom and had played Sister Prejean in the opera’s premiere in 2000. The supporting cast was quite good. I thought Mayes had the best lyrical moments, such as “every things gonna be alright,” when bluesy, rock elements entered his arias. The music overall was fine, but I kept thinking, “Jake, you should have taken this further in mixing New Orleans style music and opera.” I think that some mixing of genres might be a worthwhile direction for opera to go. Interestingly, next up for WNO is “Champion” by Terence Blanchard, which is described as an “opera in jazz”.

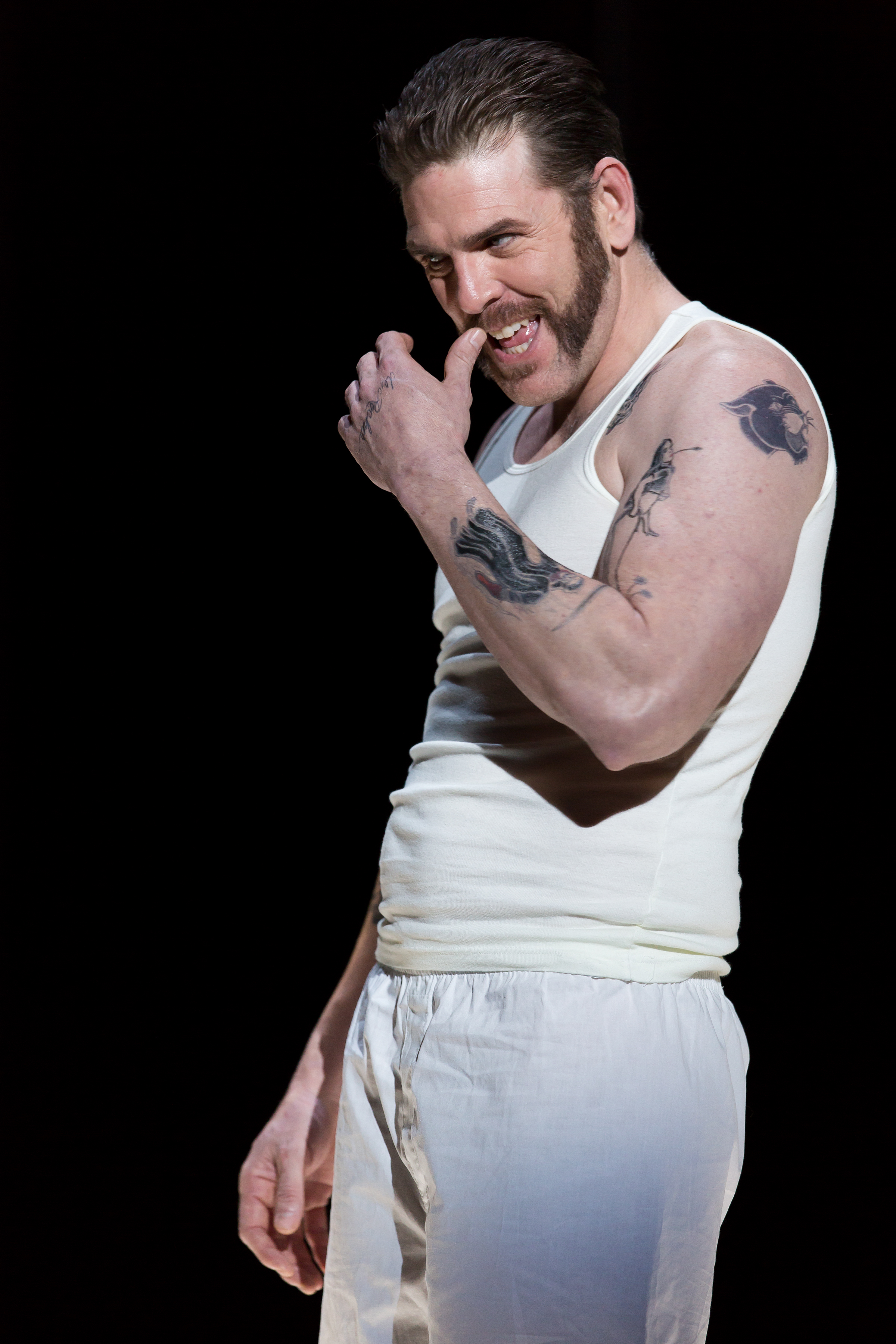

Photos above of Michael Mayes as Joseph De Rocher are by Scott Suchman and courtesy of Washington National Opera. I offer them here to make a point about how our prejudices come into play so quickly and often irrationally in stressful situations. Given only what you know now, which man in these two photos would you be more likely to offer a stay of execution? The movie's greater ability to show details allows it to make this point even more completely than the opera. In the movie, he makes statements to journalists to the effect he thinks Hitler was a great man. Guess how this influenced his case?

I realize this blog report is long on background and short on comments about the WNO performance, but my strongest reactions were to the story, and I think the telling as an opera was very effective at leading me to become immersed in the story. I recommend you go. It is a powerful artistic and human experience. I did hear one couple talking as they exited the theater who agreed it was the best WNO performance of the year. For more comment on the WNO production and new opera versus old opera, see the links to professional reviews in the side bar to the right (at the bottom on smart phones).

There are four more performances of Dead Man Walking: March 3, 5, 8, and 11. There are plenty of good, including cheap, seats available. Champion begins a run on March 4.