Champion is about a fighter whose blows caused the death of an opponent. Champion is about the impact of being a black homosexual on a man’s life. Champion is about a man’s attempt to come to terms with what it means to be a man. You can take your pick which you want it to be, or enjoy all three. I somewhat expect that your age might have something to do with your choice. In fact, I wish I could read a review of this opera by a young person. Your choice might also be affected by whether you are black and/or gay. It was synchronistic that WNO’s production came shortly after “Moonlight”, about a young black man dealing with his homosexuality, had surprisingly won the Oscar for best picture. I think Saturday night’s audience was more diversified than usual for opera at the Kennedy Center, and there was an eruption of applause when Griffith uttered the opera’s signature line, “I killed a man and the world forgave me; I loved a man and the world wants to kill me.”

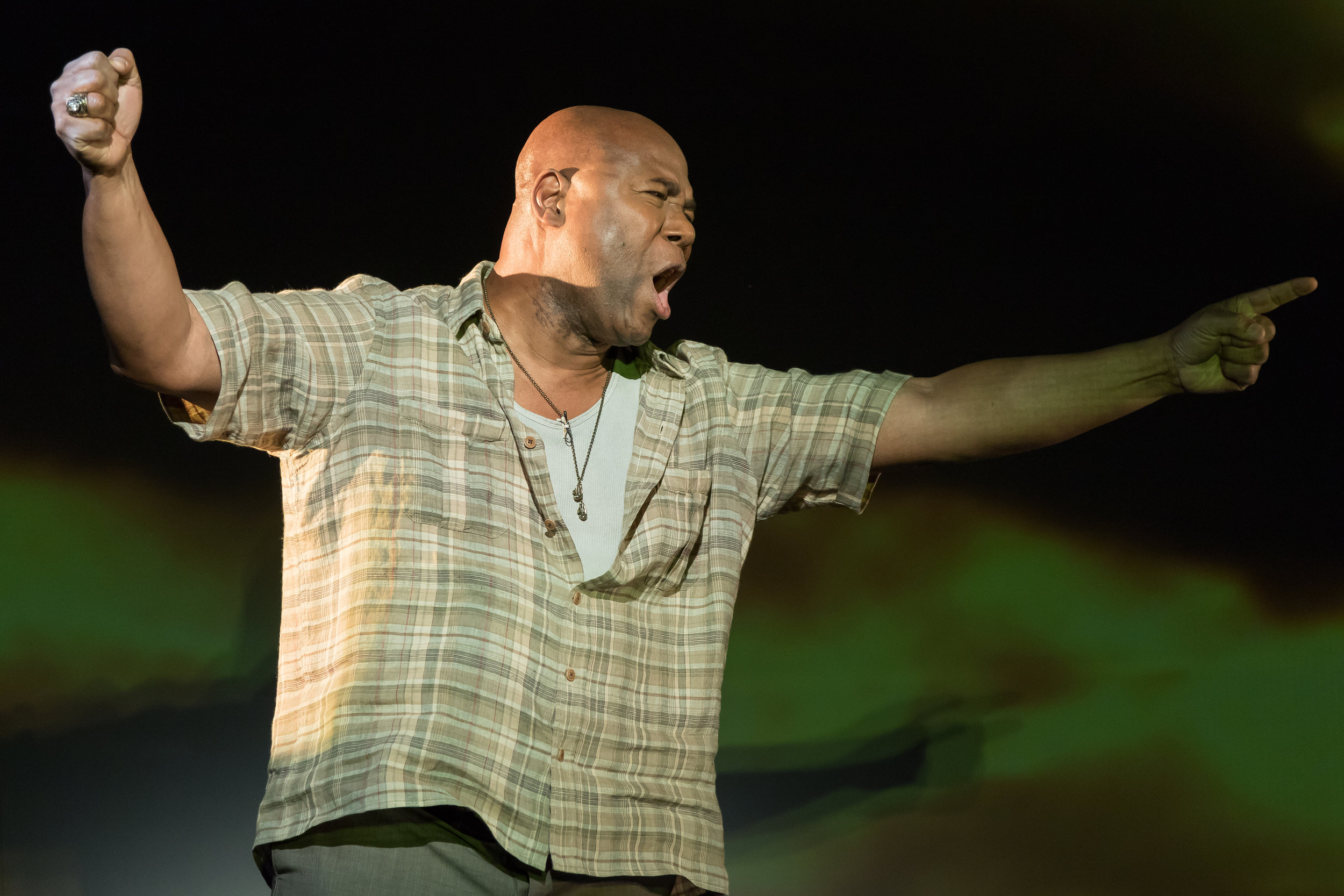

Old Emile, Arthur Woodley, from his nursing home room looks down on Benny "The Kid" Paret, Victor Ryan Robertson, young man Emile, Aubrey Allicock. Photo by Scott Suchman and courtesy of Washington National Opera.

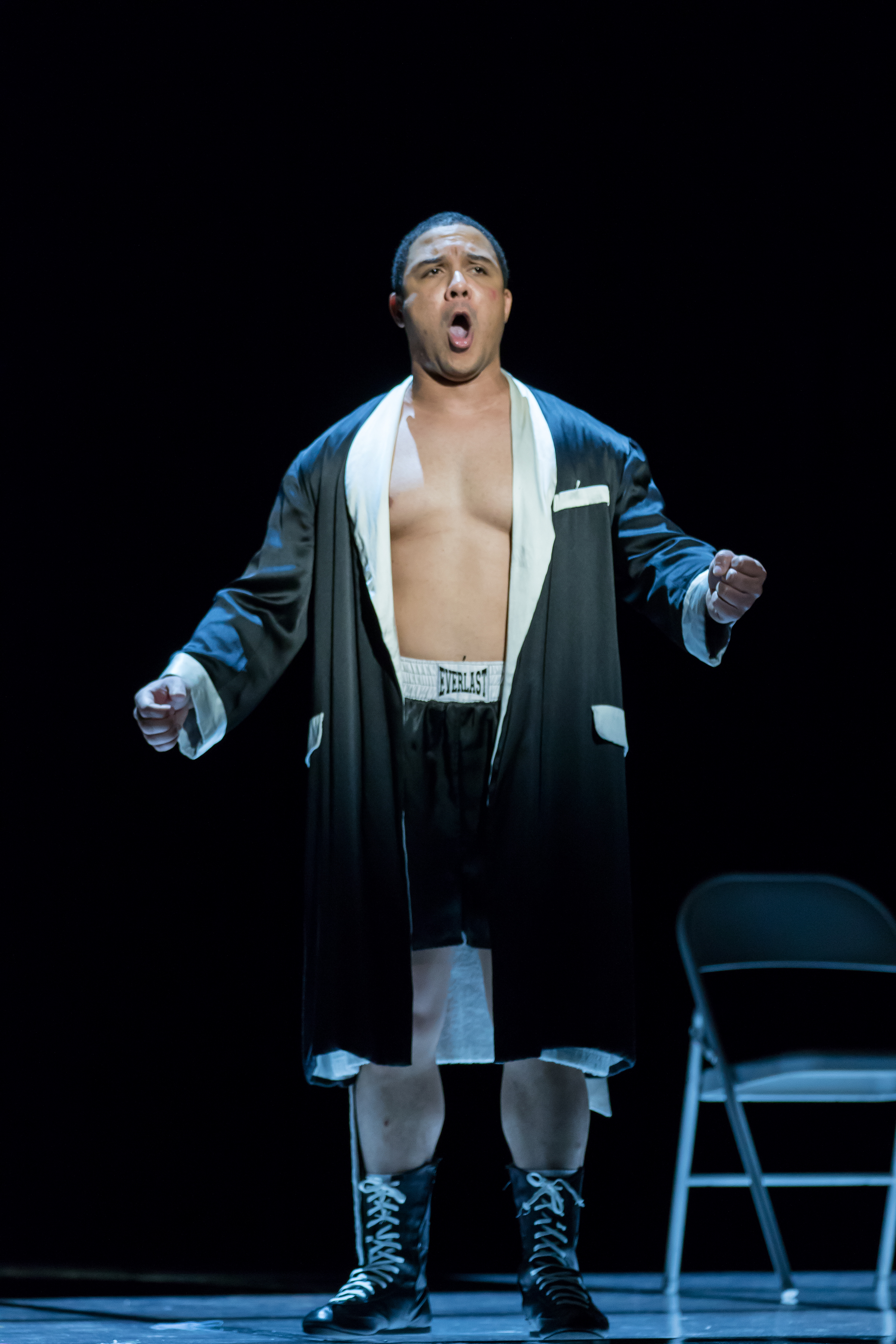

The music in this “jazz opera” by composer and jazz artist Terence Blanchard and librettist and playwright Michael Christofer is quite pleasing. I thought that it was only a couple of memorable arias away from greatness. I liked the mixing of jazz and opera, but even more jazz direction could have been used effectively. The libretto was clever and effective at communicating Griffith’s struggles through his entire life, but its use of repetition began to wear on me in later sections of the opera to the point of become a little mind-numbing. The staging was well-done and effective overall. Three Emile Griffiths were used, as a boy, a man, and an old man. This covering of the entire life of a man offers insights and perspectives on life that cannot be achieved by time-focused stories. I can identify with each stage of Griffith’s life, but I wonder what younger viewers might focus on; again, that review by a young person might help. The scenes were substantially enhanced by the clever use of screens on both sides of the stage and the back of the stage which projected images of Griffiths Virgin Island homeland and New York City. The fight scene’s use of slow motion and stop action were effective, but for me it pulled its punches in not emphasizing those final 17 blows that likely caused Paret’s death. I thought Griffith’s fierceness was also underplayed.

Griffith, Aubrey Allicock, knocking Paret, Victor Ryan Robertson, out. Photo by Scott Suchman and courtesy of Washington National Opera.

In an overall excellent production, the stand out performer for me was Arthur Woodley who portrayed old Griffith. Woodley has this rich, warm bass voice the you want to snuggle up to and in his jazzier numbers you got the feel he could sing that genre too. Young man Emile was played by baritone Aubrey Allicock and although he sang well, he was not menacing enough to me to play Emile as effectively as I wanted. Allicock portrayed him as a lost young man being tossed about by the waves of his life’s waters. More menacing was tenor Victor Ryan Robertson who sang beautifully. Opera star, mezzo soprano Denyce Graves played Emile’s mother, an important figure in Emile’s life, and her aria early in the second act was quite strong and emotionally affecting. Baritone Wayne Tigges who played his manager was ill and his singing was done off stage by Samual Schultz. Early Tigges came across as a caricature of a boxing manager, but his aria also in the second half was touching.

Arthur Woodley as old Emile, Aubrey Allicock as young man Emile, and Denyce Graves as Emile's mother. Photos by Scott Suchman and courtesy of Washington National Opera.

For me, personally, attending the opera was a failed attempt at redemption. At least that is what I thought initially. You see, as teenager, I watched on television the 1962 prize fight of the real Emile Griffith versus Benny Kid Paret. I was a fan of Griffith and was rooting for him to knock Paret out. I was excited when he stunned Paret in the 12th round, but then Paret fell back, helplessly on the ropes in a corner of the ring, and Griffith pummeled Paret’s undefended head with a series of 17 vicious blows over seven seconds. I realized, even before the slow-to-respond referee, that it had gone too far. They took Paret out of the ring on a stretcher and ten days later, never coming out of a coma, he died. I read the newspaper each day to see if he had recovered. I felt sick to my stomach. I had rooted for the beating this man received, though not for the last blows, and I had assumed his injuries would be temporary. When the news came that he had died, I lost my interest in boxing. I had seen the end-point of watching men beat each other senseless, and at that time, the later-in-life mental problems suffered by boxers were largely unrecognized. I must say in Griffith’s defense that he had no desire or intent to kill his opponent, even though badly taunted by Paret for his secret homosexuality. Boxers are taught that when your opponent is weakened to move in and land your best punches to finish them off. He was simply playing the game as it is played and was not blamed. There were later suggestions that Paret had not fully recovered from a previous fight. Nonetheless, Griffith felt guilt for his entire life.

So, where am I now with Champion? It was not the catharsis I wanted, but it was artistically excellent, an illuminating opera covering the life of a man who led an extraordinary life. In the end, seeing Griffith’s life-long struggles at least has led me towards acceptance, acceptance that life gives us challenges against which we struggle driven by both our good intentions and our human needs and weaknesses. The son of Benny Paret told Old Griffith that the forgiveness Emile sought must come from himself, and so must forgiveness for the guilt I feel come from my own heart. I’m not sure I’m there yet, but Champion helped put it in perspective.

There are four more performances scheduled for Champion: March 10, 12, 15, and 18. Good seats remain with prices $35 to $250. Don't be afraid of the cheap seats - the view is good and the sound is great! The language at times is explicit. Interestingly, while the characters spoke the F-word, the supertitles listed it as F**k.