National Symphony Orchestra logo; courtesy of the National Symphony Orchestra

A couple of weeks ago I noticed an ad for the National Symphony Orchestra’s performances of Verdi's Requiem on March 22, 23, and 24. Typically, that would have been my last thought about it. But for reasons known only to the divine, my awareness of the performances keeps re-emerging and has since hijacked my desire to blog about anything else. Why? I love Verdi’s operas, but I’m not religious though I claim a spiritual side, and requiems sound like something you should sit through dutifully and respectfully, keeping an eye on your watch. In my struggle to subdue this emerging directive, I asked myself whether I should even attend a requiem, which I imagine to be religious music for a religious service; I wish no disrespect to the true believers. Interestingly, Verdi himself was a non-believer, or at most, “a very doubtful believer”; so, I suppose I can’t break away from this compulsion out of respect for religious practices. Thus, I am compelled to explore further what requiems are, how Verdi came to write one, and what we might anticipate that will be unique to a requiem written by a great master of opera and specifically by Giuseppe Verdi.

Drawing by artist Osvaldo Tofani of the second performance of Verdi's Requiem at La Scala in Milan in 1874. In the public domain, obtained from Wikipedia.

A requiem is the musical portion of the Requiem Mass, known as the Mass of the Dead, whose text provides the libretto for Verdi's Requiem and derives from the text for the Catholic Mass with addition of a poem for the Dies Irae ascribed to Thomas Celano from the thirteenth century and deletion of sections dealing with joyful aspects of worship. The term requiem comes from the Latin meaning rest or repose; so, the Requiem Mass is intended to put the dead to rest and can be performed for one or more people, most typically as part of a Catholic funeral. Like music and religions, themselves, requiems have followed an evolutionary path. They have even been adopted by churches of other faiths and have taken on a musical life of their own, and now are often performed as works of art, concerts separate from church services. Requiems can also be written to honor prominent deceased individuals, and this was the case with Verdi. However, it would be a mistake to think that separating requiems from church separates them from religion, a point I will return to later. We must also bear in mind that Verdi was Verdi and representing drama, passion, and humans under stress in music were part of his art, so one would be surprised if a Verdi requiem were merely somber and consoling. In fact, the Verdi Requiem is sometimes called an ‘opera in disguise’ or more correctly in musical terms an oratorio. Conductor Hans von Bulow, his contemporary, called it “Verdi’s latest opera, though in ecclesiastical robes”; he later recanted that opinion. Nonetheless, one modern commentator lamented that it took religious music, “…out of the sanctuary and into the concert hall; out of its true setting as prayer, and into something that resembles operatic entertainment.” However, the same author, found sacredness in Verdi’s Requiem because of the “words”, which are primarily from the traditional Requiem Mass, and eventually he lays claims to Verdi – though not a practicing Catholic, he was nonetheless a “Catholic soul”, the author’s way of coming to terms with a great work of sacred art written by a non-believer; but no question, it may be an opera, theatrical in nature, or an oratorio, but Verdi’s Requiem is certainly a religious work.

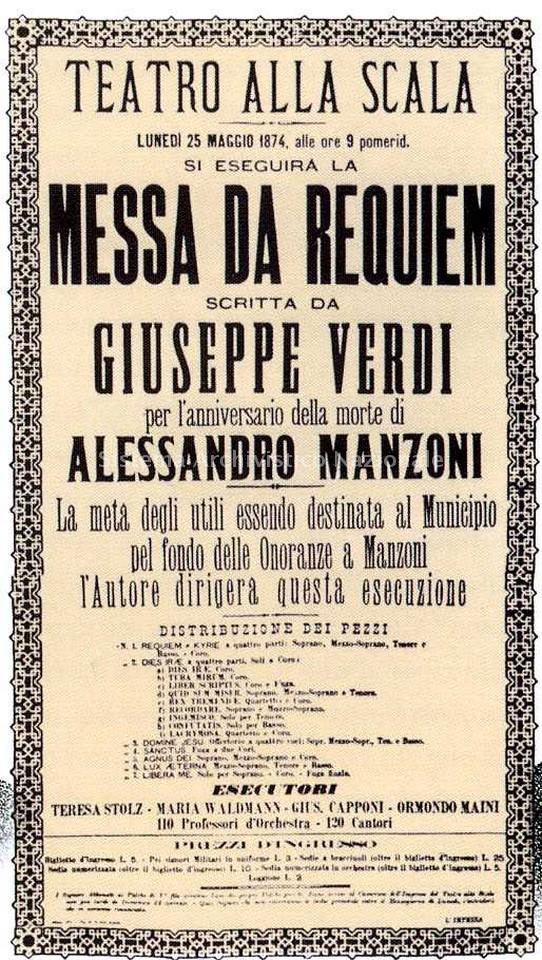

Poster for the La Scala premiere, 1874. In the public domain, obtained from Wikipedia.

The official title of Verdi’s Requiem is Messa da Requiem per l’anniversario della morte de Manzoni, 22 maggio 1874, and we will return to Mr. Manzoni, but the story of this Requiem in his honor starts with the death of Italy’s great, perhaps greatest, composer, Gioachino Rossini in 1868. Verdi was moved to propose a requiem for Rossini to be written by the greatest composers in Italy, each writing a different section of a total of 13 sections, with Verdi writing the last section. This effort was officially to honor Rossini, but the undercurrent was to play to the nationalist fervor to reunify Italy, which at that time was occupied by several countries. The effort fell apart at the very end due to disagreements. The Requiem for Rossini was finally performed in 1988. Verdi’s contribution was the last section, the Libera me, which was to be put to additional use. One of Verdi’s national idols was poet and author Alessandro Manzoni, whose novel “I promessi sposi” (“The Betrothed”) made him something of a focal point of Italy’s rising nationalism at the time. Reports are that Verdi was unable to bring himself to attend Manzoni’s funeral, but instead composed the Requiem, which was presented the year after Manzoni’s death. Verdi is said later to have driven his wife to church each Sunday, but did not attend himself. I think it is fair to speculate that some of Verdi’s interest in composing a requiem at this point in his life may have arisen from seeing ahead to the end of his own life with unresolved religious issues. Regardless, all of the issues I have mentioned taken together certainly point to the Requiem being spiritual and sacred in nature.

Maestro Gianandrea Noseda. Photo by Tony Hitchcock; courtesy of the National Symphony Orchestra.

Fair enough, but if I attend, will I be glancing at my watch? First, we should bear in mind that this is a 90-minute performance, not your typical three hours for an opera. And I have already mentioned that Verdi’s Requiem is more dramatic and even theatrical than the typical requiem. It is also called a mammoth work. Not only will next week’s performances include the National Symphony Orchestra and four soloists but will also include the Washington Chorus and the Choral Arts Society of Washington. The appeal is further enhanced by the fact that three of the soloists are opera stars who just appeared in Washington National Opera’s production of Verdi’s Don Carlo: soprano Leah Crocetto who played Elizabeth of Valois, Eric Owens who played King Philip, and Russell Thomas who played Don Carlo. Critics were unanimous in their praise of their performances; it is a special treat to have them return for the Requiem. Similarly talented and accomplished mezzo-soprano, Veronica Simeoni, will join this stellar cast. It is also worth noting that Verdi’s Requiem is something of a specialty for NSO’s director Gianandrea Noseda. The Requiem provides the conductor with considerable leeway, and the NYTimes said of a recent performance at Lincoln Center in NYC by NSO’s conductor, “Mr. Noseda, an experienced Verdian, played the work’s theatricality to the hilt.” No watches needed.

clockwise: Leah Crocetto; Eric Owens; Russell Thomas (photo credit to Fay Fox); Veronica Simeoni; all photos courtesy of the National Symphony Orchestra.

As background for this post, I began to listen to a recording of the Requiem. The music quickly snapped my head to attention and I turned it off. I decided on the spot that I wanted to make my first hearing be "live". Live is always better but for some works live is much, much better, especially choral works. Some snippets from additional reading: includes a reworked Libera me from the Requiem for Rossini; wonderful symphonic music; virtuosic solos; Verdi ensured each soloist has equal time, but also uses them in combinations; stand out accents by the base drum and punctuations by trumpet fanfares; chanted somber sections and two fugues; music evoking terror in the Dies Irae section which constitutes nearly half the work; and evoking in the end, hope. I am anticipating powerful moments when the concert hall will be awash in a wall of sound.

The Washington Chorus; photo by Bern Bel and courtesy of the National Symphony Orchestra.

The Choral Arts Society of Washington; photo by Russell Hirshorn and courtesy of the National Symphony Orchestra.

I hope I have provided information that will help you decide on attendance for yourself, whether for love of music or opera or art, or for spiritual reasons, or because you are Italian and wish to commemorate the life of Alessandro Manzoni. Maybe you will have my experience: I have no choice but to go – the spirit has moved me.

The Fan Experience: It is important to recognize that no one will be seated after a performance begins and performances are 90-minutes without an intermission; it is imperative to be there early. Performances are next Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights - March 22, 23, 24. For the Friday and Saturday evening performances, there will be a pre-concert discussion at 6:45 pm with Classical WETA’s Deb Lamberton. Tickets range from about $20 to $110 and can be purchased through this link. From personal experience, I think some of the cheap seats in the first and second tiers might be the best listening spots.