Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi by Giacomo Brogi; Wikipedia, public domain.

Don Carlo is a…maybe…“the” Verdi masterpiece. Professional reviews (see six listed in the sidebar) all agree that Washington National Opera's version has an excellent conductor and orchestra producing beautiful music, great singers and singing producing stunning arias, but about the sets and staging, not so much agreeing, but with good agreement that it is worth attending because the good parts are really good; the most critical review says that it still manages to dazzle. And Don Carlo doesn’t come around that often. There; end of story. Buy your tickets and go see it. And from Yoda: enjoy you will.

But wait…I want my time on the soapbox:

Giuseppe Verdi’s Don Carlo came home to the Kennedy Center last Saturday evening for a two-week run (but only seven performances) after a twenty-year absence. Unless you travel to Europe you probably have not seen this opera for a while. According to Operabase for the period 2016-2019, there have been or are currently planned 75 productions of Don Carlo(s), but only three of those are in the U.S., one by San Francisco Opera in 2016, the current Washington National Opera run, and a scheduled LA Opera production in October 2018. When an opera is held in such high regard as Don Carlo is and thought by many to be his masterwork, why isn’t it performed more often in the U.S., like Tosca or La Traviata which seem to appear monthly? The common answer offered is that it is an expensive opera to produce. Ken Weiss, Principal Coach of the Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist program explained in his pre-opera talk that Don Carlo requires five, really six, top notch soloists, a large chorus, and a large orchestra. I accept the explanation that this opera is too expensive to produce very often in the U.S.; apparently opera companies in Europe have regular singers on staff, so the cost is somewhat defrayed. However, I think there might also be another reason or two that it gets passed over by artistic directors which I will bring up later, along with one why now might be the time to bring it up more often.

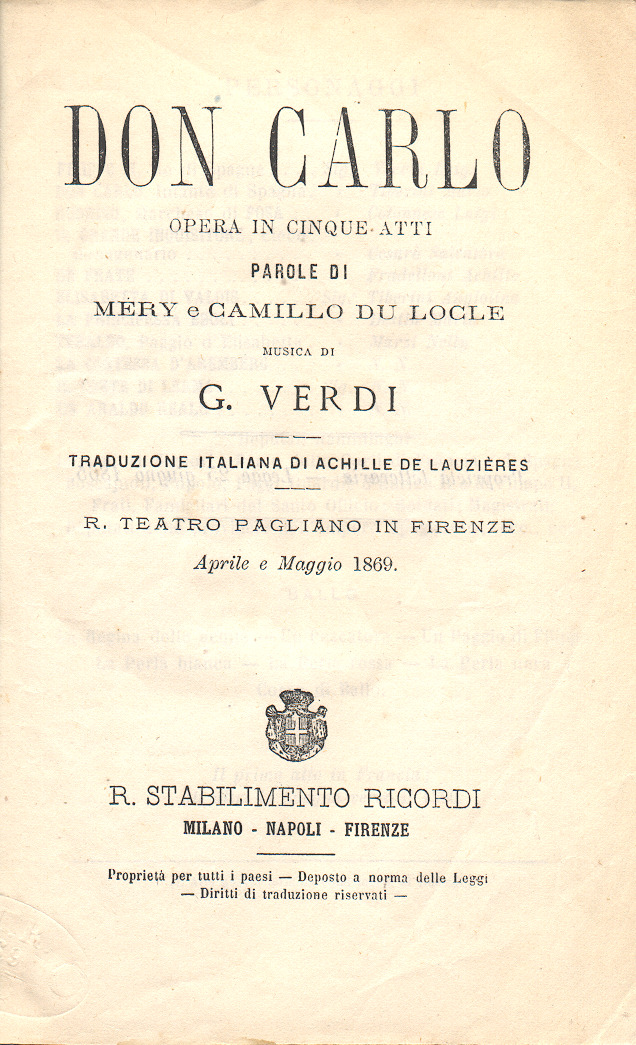

Poster from the 1867 Paris production and a libretto title page from 1869 Italian production; images in public domain from Wikipedia.

If you have seen one Don Carlo by composer Giuseppe Verdi and librettists Joseph Mery and Camille du Locle based on the play by Friedrich Schiller, you have not seen them all. Originally written as a Parisian Grand Opera of five acts including a ballet, Verdi revised it to four acts for Italy, of which several versions exist with at least one restoring the deleted act. WNO chose to go with a four act version and changed the ending. As Mr. Weiss explained in his talk, there are three levels to this opera: 1) inter-family conflicts; to cement peace with France, King Philip II of Spain has married Elizabeth of Valois, the fiancé of his son Don Carlo, but she and Carlo are still in love with each other; then there is Princess Eboli, a member of the court and secret mistress of the king, who has taken a liking to Carlo herself; 2) Philip has to deal with problems in his own country, especially the Inquisition who insist on strict adherence to Catholic Church doctrine and its preeminence; and 3) internationally there is an uprising in the Netherlands where many Flemish citizens want to be protestant, and Spanish authorities are clamping down hard; the Flemish case is being pushed by Rodrigo, Marquis of Posa, an aide to Philip, who is trying to get Carlo to join the cause. Philip is dealing with a wife trying to be faithful to him, but doesn’t love him, a rebellious son, an aide pushing him to allow the Flemish to worship as they wish, and an Inquisitor who demands complete loyalty to the Catholic church. What was the great one trying to do engaging such an intricate plot? Author David Kimbell (“The New Penguin Opera Guide”, ed. Amanda Holden, 2001, p.977) says he was trying to do what Verdi always tried to do: “He never wavered in his loyalty to values he inherited in his youth: a good opera was an opera that was acclaimed all over Italy by enthusiastic audiences in packed theatres; its object was the exploration of human passions and human behaviour in situations of extreme dramatic tension, and its principal means of expression was the fusion of poetry and music in dramatic song.” It also helps explain why after completing his commission to write Don Carlos as a French Grand Opera, he completed additional versions as Don Carlo in Italian.

left: Russell Thomas as Don Carlo. right; Leah Crocetto as Elizabeth of Valois. Photos by Scott Suchman; courtesy of Washington National Opera.

I agree with the professional reviews about the singers and their performances. Mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton as Eboli demonstrates she has arrived and is a commanding voice and presence on the stage. Not far behind was soprano Leah Crocetto, who played Elizabeth as an obedient subject of the king, but also showed she could use her lovely voice to reign down fire when called for. Venerated bass-baritone Eric Owens as Philip and tenor Russell Thomas as Don Carlo gave the quality performances expected. Bass Andrea Silvestrelli made the Inquisitor a threatening presence. A surprise for me was Quinn Kelsey as Rodrigo, whom I had not heard previously; a more beautiful, lyrical baritone I have not heard. In fact, he often sounded like he was in a different opera, a bel canto opera; perhaps Verdi wrote his role that way? The minor pants role of Tebaldo was played in a sprightly and courtly manner by the versatile mezzo-soprano Allegra De Vita. The orchestra supplied the beautiful music under Maestro Philippe Auguin’s direction, his final scheduled production with WNO, and the large chorus was a pleasure to the ears; kudos to Chorus Master Steve Gathman.

left: Eric Owens as King Philip. right: Jamie Barton as Elizabeth of Valois. Photos by Scott Suchman; courtesy of Washington National Opera.

Fault has been found by professional reviewers with the staging and the sets, though opinions vary. The most dramatic difference of opinion occurs between the Kennicott and Salazar reviews. Mr. Kennicott in his Washington Post article felt the opera had been pared and dumbed down in sets and staging, while Mr. Salazar, who writes for OperaWire thought Director Tim Albery had cleverly used the staging and sets by Andrew Lieberman to signal how the events in Don Carlo mirror what is happening today in government and politics. He also thinks the director connects with current events by having a crowded theater audience hear a gunshot coming out of nowhere; I didn’t make that connection myself, just resented the shock to my nerves. The set and the staging worked for Mr. Salazar and he has raised some interesting interpretations which may or may not have been intended by Mr. Albery and Mr. Lieberman. Mr. Kennicott, who reviews opera occasionally is the Post’s Arts and Architecture Critic; it is perhaps to be expected that he would emphasize the opera’s visual aspects. I found both reviews to be thought-provoking reading.

left: Quinn Kelsey as Rodrigo and Russell Thomas as Don Carlo. right: Eric Owens as King Philip and Andrea Silvestrelli as the Grand Inquisitor. Photos by Scott Suchman; courtesy of Washington National Opera.

This was my first Don Carlo, so I can only comment with the perspective of having attended Saturday night’s performance. Initially, I was impressed by the set with the tilted stage and cloister walls drawing in the rear to an octagonal ceiling, but that set served, with some minor modifications, for the entire opera and thus it became weary; the ceiling was open in the second half to reveal a clouded sky and I became involved in finding angry god faces in the clouds (at least three). Even if Mr. Salazar is right, I think in the case of Don Carlo subtle allusions are not what’s needed. Sets and staging that plainly support the plot would have been helpful; as I said before, there is a lot going on here. The points made by Mr. Kennicott about the decisions to not use an act that clarified the relationship between Carlo and Elizabeth and the effect of the chosen ending on the drama are on target. One point made by Mr. Salazar and echoed by others is the relevance of the story to current day and that does argue for this opera receiving more attention in the U.S.

Here is my problem with Don Carlo which I think may lessen its demand: Don Carlo could have easily been titled Philip or Elizabeth or Eboli or Rodrigo; I might even vote for Inquisitor; everybody gets attention, but no one gets enough. As a result, I could not get viscerally into the story or develop strong feelings for any of the characters. They are presented as stick figures that are fleshed out by arias and the singers in limited ways. Eric Owens’ aria to begin the second half gives some depth to his character as he laments his inability to garner Elizabeth’s love and is then bullied by the Inquisitor. Leah Crocetto’s response to Eboli’s intrigue showed a new side to her character. Rodrigo probably receives the most attention of all, motivated by concern for the Flemish and torn between Philip and Carlo. What we essentially get is an expose of corruption in the Spanish monarchy and that’s a fine Verdi opera. However, these days tune in to CNN or Fox News and hear it daily. What’s lacking that is needed for modern day audiences is greater character development and greater coverage of how these people come to make the decisions they do and how it affects their subjects, starting by including the omitted first act. Perhaps for audiences in Verdi’s day accustomed to royalty the plot cut closer to home. Modern American audiences need to identify with these distant characters and their motivations. I don’t know how this can be effectively achieved in a three-hour opera, which is equivalent to maybe a two hour play. Verdi should have made Don Carlo a three-opera miniseries. Suppose we first had seen an opera about the love affair of Elizabeth and Carlo against the backdrop of Spain/France peace negotiations, ending with his father announcing she would be his bride; and then one about Rodrigo and the suffering of Flemish protestants; now we are set up to bring in the king and the Inquisitor for the finale. If Verdi were alive today and did that, he could sweep the Emmys and Golden Globes.

The Fan Experience:

There are five remaining performances of Don Carlo, March 8, 11, 14, 16, 17; note that there are different singers in the lead roles for the March 16 performance.

For Don Carlo, I strongly advise attending the excellent pre-opera talk by Ken Weiss which takes place an hour prior to showtime, or at least reading a synopsis with background information; otherwise, you will likely miss a lot of what is going on, and there is a lot going on.